At EdgePoint, we pride ourselves in having an eye for the peculiar, and in the current monetary malaise there’s no shortage of enigma to feast our eyes on. In today’s market, in the words of legendary investor Charlie Munger, anyone who is not confused doesn’t understand the situation very well. Shown below is one puzzling example: what you see is a newly issued one-year euro-denominated General Mills, Inc. bond offering an interest rate of exactly 0.000%. As an investor, talk about a tough way to make a lot of money.

Source: Bloomberg LP. General Mills, Inc. 0.000% Notes, due 2020 8-K Form.

It is fascinating to think that any business could issue an unlimited amount of debt with an interest rate of zero and, so long as the debt could be refinanced at maturity, would never run into issues servicing that debt. In fact, you wouldn’t even need the business; as I write this commentary, I could just as well issue $100 billion in interest-free bonds and my bondholders could be content knowing that I will easily make payments on exactly what was promised. Still, the central bankers of the world think this is somehow beneficial to the overall economy.

It’s not to say that many businesses have gotten away with issuing bonds that promise to pay absolutely nothing, but interest payments have undoubtedly come down in a very meaningful way across the fixed income spectrum. In such an environment, corporate bond issuers have done exactly what you would expect them to do: they’ve issued an enormous amount of debt. As shown in the figure below, non-financial corporate debt outstanding (i.e., debt issued by businesses other than banks) has increased by almost 50% to nearly $9 trillion since troughing at a post-financial crisis low of roughly $6 trillion.

Nonfinancial corporate debt

2000 to 2018

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, "Late-cycle risks in credit", March 2019. Nonfinancial corporate debt securities (commercial paper, industrial revenue bonds, corporate bonds) plus loans (depository institutions loans, other loans and advances, mortgages).

Over the past 10 years – again, since the financial crisis – corporate profitability has also grown, but for debt-issuing businesses profits have not kept pace with the 50% increase in outstanding debt. As shown in the chart on the left-hand side below, gross leverage for investment-grade issuers in particular (as measured by total debt-to-company profits) is hovering above prior highs set in the troughs of previous recessions. This is an important point since it means the last time leverage ratios were at or near current levels, it was because business profitability was depressed and not because new bond issuance was through the roof, as is the case this time around. Today, the economy is strong and profitability is high, which means this leverage ratio could become really ugly really fast in the event of a downturn.

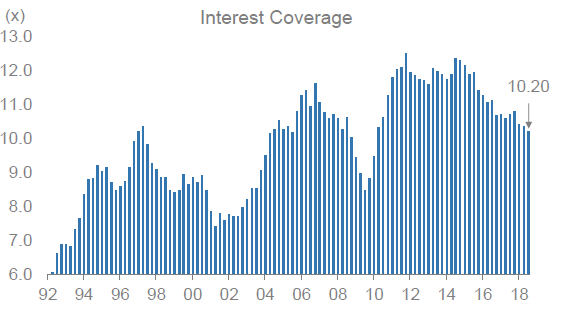

Gross leverage and Interest coverage

1992 to 2018

Source: Morgan Stanley, "U.S. Corporate Credit Strategy Outlook", March 2019.

But just like I could easily make interest payments on $100 billion of debt with a 0.0% interest rate while sitting at my desk, these same corporate issuers with high amounts of debt relative to current profits still have historically low interest payments to make. Accordingly, as shown in the chart on the right-hand side above, interest coverage ratios remain relatively high by historical standards. Despite the high level of debt, interest payments are easily covered by corporate profits.

Interest coverage ratio:

used to determine how easily a company can pay its interest expenses on outstanding debt. The ratio is calculated by dividing a company's earnings before interest, taxes and depreciation (EBITDA) by the company's interest expenses for the same period.

You can imagine the dilemma for the poor ratings agency analyst trying to figure out if a business has incurred an excessively burdensome level of borrowings. Low interest rates have meant fixed interest payments remain easy to meet, while at the same time investment-grade companies have rarely had more debt outstanding as measured against corporate profitability. With so many investment-grade-rated businesses borrowing so much money at such low interest rates, the amount of BBB-rated debt – the lowest rung of investment-grade debt before being downgraded to junk – has grown more than fivefold since the financial crisis, to close to $2.5 trillion.

BBB-rated debt vs. BB-rated debt

2000 to 2018

Source: J.P. Morgan, excludes emerging market issuers. The amount of BBB-rated debt has increased by 5.3x since 2007, while BB debt has increased 2.3x. The BBB market is now 4.8 times larger than the BB market.

You might be thinking this simply means there are many BBB-rated corporate bonds to choose from. The problem lies in the fact that BBB-rated bonds tend to become junk-rated bonds when we enter an economic downturn. Just how many bonds will get downgraded from investment grade to high yield depends in large part on how long any downturn lasts, as well as the condition of corporate balance sheets at the time. Using one approximation that applies historical downgrade patterns to current levels of BBB-rated debt, JPMorgan analysts estimate that as much as $494 billion in investment-grade debt could be downgraded to high yield over a three-year period during the next economic downturn.i

That’s a lot of new high-yield debt that needs to be accommodated! Where things start to get complicated is when you realize this $494 billion in newly created high-yield debt needs to squeeze into a global high-yield bond market that today totals almost $1.3 trillion, as reflected by the yellow layer in the chart below. In the past, high-yield bond investors benefitted from the easy pickings of so-called “fallen angels” that arise when investment-grade fixed income mandates that are prohibited from owning high-yield bonds become forced sellers as a result of a downgrade. However, we are opening a whole new can of worms when the buyer base of high-yield bonds needs to expand by 40% just to absorb newly downgraded debt. This could present a real conundrum in the high-yield market.

Source: Morgan Stanley Research, FTSE Fixed Income LLC. Supply from above when the cycle turns: BBB par outstanding now ~2.5x as large as the full high-yield index.

Perhaps an example is in order

Call us crazy, but this imbalance excites us. The scenario that we just walked through would almost certainly cause some distortion in high-yield markets, but there’s nothing like body-checking the applecart to shake out some mispriced bonds. Let’s walk through an example.

Below we’ve listed the six largest BBB-rated bond issuers in the U.S., who together account for $400 billion of the previously identified $2.5 trillion in BBB-rated debt outstanding. Let’s imagine a scenario where AT&T makes a very large acquisition at a time when there’s major disruption in the way internet service is delivered to the home. Households are relentlessly “cutting the cord” on traditional TV service and there’s an arms race with very-well capitalized and borderline irrational competitors for high-quality, star-studded video content at a time when audiences are inundated with low-cost viewing options. All hypothetical, of course. In our scenario, AT&T revenue flatlines, capital expenditures rise and margins are squeezed – ’lo and behold, the company is downgraded to junk status.

| Index debt (US$ billions) |

|---|

Suddenly, investment-grade fixed income managers who hold AT&T bonds find themselves forced to sell $95 billion worth of AT&T debt into a $1.3 trillion high-yield bond market. In other words, the high-yield market needs to expand by over 7% just to accommodate one newly downgraded issuer. Here is the sequence of events that would unfold: any existing high-yield bond fund looking to add AT&T to its holdings would need to sell existing high-yield holdings in order to do so. This means that otherwise healthy bonds will be discarded in favour of the formidable AT&T, putting pressure on the discarded bond’s price. Eventually, this price will need to be low enough to offer a yield that entices new money into the high-yield market.

Perhaps our own high-yield bond holdings will be among those that are discarded. Let’s walk through an example of a high-yield bond holding. Era Group Inc. is a helicopter flight services company that ferries offshore oil and gas workers to-and-from offshore platforms primarily in the Gulf of Mexico. We bought the bonds in the fourth quarter of 2016 in the EdgePoint Global Growth & Income Portfolio and EdgePoint Canadian Growth & Income Portfolio when anything related to oil and gas – particularly offshore oil and gas – was being rejected by the market, much like the situation is today. Our view was that Era’s prudent and efficient management team could manage the downturn without any uptick in activity (demand improvement). At the time, Era’s 7.75% bonds due in 2022 were trading at a price of 96 to yield 9.0%.

Bouncing along the bottom of the oil and gas cycle, over the past two years Era has continued to generate cash from operations and sell non-core assets. This has allowed the company to dramatically improve its financial position by paying down debt and stockpiling cash, as shown below (adjusted for one more asset sale in the first quarter of 2019). The value of Era’s net outstanding debt as a percent of the value of the helicopters that it owns has improved from 30% when we first bought the bonds to just 12% at the end of 2018. This means we think the helicopters are worth eight times the value of the bonds we own, adjusted for cash. But the market still doesn’t like oil and gas, so even today the bonds trade just above 99 to yield 8.0% to maturity.

| Era Group Inc. (In US$ millions) | 2016 | Q1 2017 | Q2 2017 | Q3 2017 | Q4 2017 | 2017 | Q1 2018 | Q2 2018 | Q3 2018 | Q4 2018 | 2018 |

|---|

In our hypothetical example, if the downgraded AT&T caused our fellow bondholders in Era Group’s 7.75% bonds due in 2022 to discard their helicopter holding in favour of the telecommunications giant, we would gladly relieve them of their burden, although we might try to pay a price closer to our original 96. If our fellow bondholder happens to be an index fund that must trim its Era bond holding in favour of AT&T, we’ll be sure to bid with an even bigger discount.

Concluding remarks

It’s almost certain that the incredibly low interest rates we’ve experienced over the past several years will, at some point, impact markets in ways we cannot foresee. Today, one of the most glaring distortions in credit markets has been the rapid expansion of BBB-rated corporate debt, matched only by the equally glaring leverage ratios that characterize BBB-rated issuers. In the next economic downturn, as corporate profitability falls, the magnitude of low-rated investment-grade debt that might experience a downgrade will almost certainly have an impact on corporate bond prices. But any pricing distortions caused by investment mandate constraints that create forced sellers, or by other technical factors unrelated to company fundamentals, present nothing but an opportunity that we’ll gladly explore for our Portfolios.