Forgetting the forecasts - 2nd quarter, 2019

Investing in the financial markets is often a humbling experience and, so far in 2019, that has definitely been the case. Most fixed income managers have kept their focus on the dramatic decline in interest rates around the globe. Much has been said about the level of low interest rates since the Financial Crisis, but this time last year the consensus was that the economy and central banks were finally in a position to encourage interest rates to rise in North America.

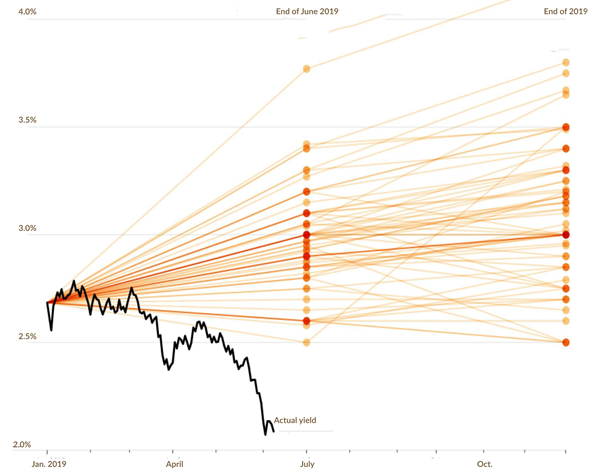

At the beginning of 2019, The Wall Street Journal surveyed economists to predict where interest rates would be in June and December of 2019. As you can see from the graphic below, not one of them came close to predicting the dramatic decline in rates and there is no reason to believe that their forecasts will fare any better at the end of the year.

Yield on the 10-year Treasury Note - January 2019 analyst predictions

Source: Avantika Chilkoti & Daniel Kruger, "Some Investors Had Hunch Yields Were About to Fall", https://www.wsj.com/articles/some-investors-had-hunch-yields-were-about-to-fall-11560072600

I’ve seen similar results posted for economists trying to predict the future price of oil or currency rates, and each time the result is basically the same. Forecasting the future is hard and humans are generally very bad at it.

While economic forecasts may make for good banter in the financial media, at EdgePoint we try to limit the amount of time spent on forecasting areas of the market where we lack an edge. The investment team has opinions on where we think rates are headed but we certainly don’t have confidence in our ability to be correct.

That being said, we can’t avoid the topic. We invest in fixed-income securities and therefore we’re exposed to a level of interest rate risk. If we could have predicted the decline in rates this year we would have loaded up the Portfolios with long-term bonds, as their price has increased materially with the fall in rates in the first half of 2019. However, that wasn’t the case and our Portfolios’ below-average duration (i.e., sensitivity to changes in interest rates) has caused us to miss out on the performance that long-term bonds would have provided.

Should we be concerned about the level of relative underperformance this year? As an investment-led company, one of our founding goals is the long-term outperformance of our portfolios. But does six months of underperformance jeopardize this goal? I often ponder this question and I continue to believe that it does not. Furthermore, I believe that trying to invest differently in light of the short-term market environment would be detrimental to our investment approach.

To reiterate, we’re committed to investing in areas of the market where we believe we have an edge. We don’t have an edge predicting interest rates and can’t invest as if we do. Setting our Portfolios’ duration isn’t an exercise in forecasting the unknowable; rather, it’s a function of risk and reward. In January of 2019 we simply thought that earning 2.68% by investing in 10-year Treasuries wasn’t earning us enough to compensate for the inherent interest rate risk. If rates had risen 0.65% instead of falling the same degree over the last six months, an investment in 10-year U.S. Treasuries would have lost 5.5%i. The room for rates to increase is certainly much higher than the room for rates to decrease. For context, the average 10-year Treasury rate in the U.S. was 4.54% since 1990ii. A return to that level spells a very poor return for investors. That wasn't a degree of risk that we felt comfortable taking.

If we don’t spend our days discussing interest rates, how does the Investment team spend their time? We focus on where our true edge lies. We’re all business analysts and find investment ideas digging through company filings, meeting with management teams and reading industry publications. Our investment approach is centred on fundamental analysis and developing an investment thesis that isn’t widely shared by others. Rather than taking interest rate risk in our fixed-income portfolio, we choose to take credit risk. We’re much more confident in our ability to analyze balance sheets of a business than to predict actions of a central bank, and history has shown that our investment approach is well suited to investing in corporate bonds.

While many fixed-income managers were trying to unravel why interest rates were falling, we were trying to better understand the businesses to which we have lent money. Rather than asking what U.S. Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome Powell will do next, we are instead asking questions like:

What will the bankruptcy of two large helicopter companies mean for future levels of competition in the industry?

Will the turnaround at North America’s largest fleet manager continue to add value, allowing the business to grow in a relatively slow growth industry?

Will exploration & production companies continue to focus on free cash flow or will the growth imperative return?

We’ll never be able to answer questions like the ones above with perfect accuracy, but we certainly have a better chance than predicting interest rates. Taking a long-term approach that’s centred on business rationale has been a fruitful way for us to take risks we understand and earn attractive returns.

As with any investor, I certainly don’t like to experience periods of underperformance, but short-term underperformance is often the cost of achieving long-term outperformance. Fretting over the direction of interest rates is unlikely to lead to actions that would benefit the portfolio. Instead, we focus on ensuring our credit analysis is thoughtful and complete, putting us in a position to outperform over the long term.

iiSource: Bloomberg LP. Average U.S. Treasury rate from January 1, 1990 to June 28, 2019.