"Price is what you pay, value is what you get." – Warren Buffet

Ask a Canadian how much a cup of Tim Hortons coffee costs and you’ll likely get a pretty accurate answer. At the very least, most of us will be able to make an educated guess and almost certainly be within the ball park. If you were suddenly told your small double-double cost $25, you’d bristle at the high price tag because you have a clear understanding of the going rate.

The value of a cup of java is well known, even by those who don’t necessarily take a daily trip to the coffee shop. Much more obscure is what Tim Hortons as a business is worth. Therein lies a big problem for the average investor. They tend to have no clue about the actual value of publicly traded companies, the very ones they invest in to build their wealth.

Stop right there, you say. You’re more in tune with the stock market than we give you credit for and happen to know Tim Hortons’ stock price. (In fact, you also know the company has been acquired by Burger King, also known as Restaurant Brands International Inc.)

Regardless, a quick Google search will pull up the current trading price of any public company. This information is readily available. Knowing what you paid for a share in a business is one thing. Doesn’t mean you can you say with an iota of certainty what the true value of that business is.

Why aren’t stocks priced like my cup of coffee?

The price of a stock (or indeed the price of anything) is just the number that a willing buyer and seller agree on. With familiar products and services like cars, haircuts and coffee, it’s relatively straightforward to grasp the price-to-value relationship. If prices on these products and services tripled, people would likely stop buying them en masse.

Not so for market investors. Why is it that stocks can have an equal or greater chance of being purchased after they’ve tripled in price? Because the tricky part about buying and selling stocks is that investors typically have no experience as company owners. They’re consumers of products and services, and their knowledge of businesses often ends there. That makes resolving the difference between a stock’s value and its price an especially baffling issue for investors. They wind up misreading supposed cues, like interpreting a fast rise in a stock as being an ideal buying opportunity. These same investors can be highly susceptible to panic selling when that stock falls abruptly.

A wolf in sheep’s clothing

Why is it that stocks can have an equal or greater chance of being purchased after they've tripled in price?

Not helping the case is that investors are led to believe the market is “efficient” in that at any given time it purportedly reflects all available information about the businesses that comprise it. The claim is that stocks are perfectly priced according to their inherent investment properties, something that all investors are equally aware of.

Were that true, we at EdgePoint would be out of a job. We believe we're presented with many opportunities where the market is inefficient. What’s an inefficient market? One in which mistakes are made and businesses are misunderstood, causing their stock prices to deviate from their real value. An efficient market implies investors always behave rationally. But being human, investors have an inherent irrational streak. They can be overly optimistic (or pessimistic), overreact (or don’t take action when they should) and fall victim to herd mentality, opting to go with the crowd instead of thinking independently and making well-informed decisions about what to do with their money. This is often the case when dealing with some unknown. People don’t know what to do when faced with challenges they’re unaccustomed to. Investing is no exception. Given that, the market can't be efficient all of the time.

A zero-sum game

Another difference between buying your morning coffee and buying stocks is that for every winner in the market, there’s an accompanying loser. The same can’t be said for your caffeine consumption. In practically 100% of market-related transactions, money gets exchanged between investors. No dollar ever comes out of the market into an investor's pocket that didn't go into the market from another investor's pocket. Investing is a high-stakes game in which you’re either making a mistake or capitalizing on someone else’s. In other words, if you screw up, your loss is some other investor’s gain.

Investment mistakes run the gamut. They include everything from not doing your homework, disregarding significant details about a business or being wholly unfamiliar with it, to misjudging information or letting emotion creep into your investment decisions. Emotionally-based investing missteps are some of the most pervasive and being able to control your emotions, especially during periods of duress, is probably the hardest skill to master.

All heart, no head

Take a look at this bar chart. Blame good ol’ emotion as a primary reason for why investors consistently perform worse than every other investment category and just barely outpace inflation.

20-year annualized returns by asset class

Your ability to manage your emotions is key to determining your outcome in the market. Unfortunately, this is where investors usually fail miserably. They’re lousy at being their own best therapist and thus get taken advantage of.

It’s almost effortless to snag a quality business at a bargain from someone whose fears about the future cloud their views about that business’s merits, most especially when they may not even know what those merits are. Explains why there tends to be more attractive buying opportunities during market downturns. Solid investments are aplenty when investors are all gloom and doom. They have only their gut feelings to latch onto and guide their decisions if they don’t know a company’s worth.

In heady times, investors face a similar problem. When they see only blue skies ahead, their exuberance dominates any lucid thought around the underlying good or bad qualities of the businesses they own.

Back to the question of why a stock is more alluring after it’s tripled in price, you can see how that phenomenon is directly a result of thinking with your heart and not your head. Investors sabotage themselves by acting on emotion, positive or negative, instead of on the facts of a business itself. This leads to stocks becoming severely overvalued when everyone is interested and unjustifiably undervalued when they fall out of vogue.

The dot-com boom of the late 1990s is an example. Companies that generated no profit and had next to no real value were selling at astronomical levels. At the time, the fundamentals of those businesses seemed meaningless. Investors wanted in on the party and that was enough for them.

A few short years after the initial bonanza, economic reality came back to haunt the market. Dot-com stocks fell 90% or more from their highs and many of these businesses went bankrupt, ultimately becoming worth less than the paper their share certificates were printed on.

There’s no worse feeling than watching the price of something plummet that you don’t know the value of.

A few short years after the initial bonanza, economic reality came back to haunt the market. Dot-com stocks fell 90% or more from their highs and many of these businesses went bankrupt, ultimately becoming worth less than the paper their share certificates were printed on.

Just as investors are apt to rush to buy a stock that they know nothing about when it’s moving up, so too are they more likely to sell it off in droves as it’s tumbling. They do this because there’s no worse feeling than watching the price of something plummet that you don’t know the value of.

You don’t know what you don’t know

Transacting in stocks on little more than a whim is speculation, not investing. Speculators ignorant to company fundamentals are liable to drive prices to extremes, while genuine investors who behave like business owners bring sensibility to the market so that over the long term, share prices reflect underlying company value.

Of course it takes extensive know-how to recognize what a business is worth. Investors able to conquer their emotions can nevertheless lack the basic tools needed to accurately value stocks. Consider the widely held belief that share-price movements in the short term somehow reflect a company’s progress (or lack thereof). Talk about completely oversimplifying the matter! A blip in a company’s share price doesn’t impact its market share, customers, costs, margins, sales, employees or earnings. The price at which investors are willing to buy and sell at in the short term isn’t all that relevant to the business itself. Think of it this way: a business’s daily share price is influenced by lots of short-term market noise whereas a business’s value is created by its assets and future cash flows.

Since companies can on occasion trade for half their value and at other periods for two, five, 10 or 20 or more times what they’re really worth, investing is neither for the faint of heart nor the ill-advised. You need the time and business acumen to be successful at it. Having a deep understanding of the businesses you own and how they’re valued will help you to think sensibly.

Investing requires broad due diligence including pouring over financial statements and other reporting resources, studying a business’s competition, meeting with its management and building financial models. It can take weeks, months and longer to properly scrutinize a company as a potential investment. You then have to figure out whether it’s trading above or below its proper value. The hope is that it’s trading for less than it’s worth and that the market will eventually come to recognize this so you can make money.

Know something others don’t

To make outsized returns, you must see something distinctive about a particular opportunity. We refer to the unique perspective you need to have on a business to gain an edge over other investors as a proprietary insight. If you merely know what everyone else already knows about a company you’re out of luck. The market’s collective judgement will already be reflected in its share price. The average investor seldom has this unique outlook. They buy Apple because its phones are popular or utilities companies for their dividend payouts. Thing is, everyone knows these facts. When investors base decisions on common knowledge, their reward is almost always subpar investment performance.

Proprietary insights revolve around identifying how a business will look different in the future and whether the market’s view of that business is unlike yours. If you believe a company will be bigger and the market isn't asking you to pay for that growth, you have to question why. If you have reason to believe the market’s judgement is wrong, then you may have a proprietary insight.

Proprietary insights typically evolve from meaningful research acquired over time. You can’t filter for them and there’s no formula for how to nurture them. They develop in unpredictable ways, sometimes unconsciously. At EdgePoint, we generate these insights by accumulating facts and applying reasoning to those facts. The majority of the information we gather will prove worthless in fostering a proprietary view. It may help us to know what others know, but no more than that. The rare time we can logically connect the insights that really matter, we gain an idea that isn’t widely shared by others.

There's no worse feeling than watching the price of something plummet that you don't know the value.

Play the long game

Say you’re successful in uncovering a proprietary insight about a business. Do you then have the conviction to see it through to its logical conclusion, to the point where you profit from it? Given that market and business values tend to be more closely aligned over the long term and that short-term price volatility is unavoidable, your resolve will most certainly be tested. You need to be able to block out daily noise – about macroeconomic concerns, stuff in the news and from other investors (including your hairdresser) – and keep your eye on the prize. No small feat as this often demands that you be willing to look wrong in the short term to be right in the long term, which is part and parcel of having a unique view about a business’s prospects. It can be hard to imagine a different future from the present day, much easier to get distracted by the current hullabaloo and forget why you originally invested in the first place. Self-doubt is a powerful adversary, especially when combined with the tendency to assume near-term trends will continue indefinitely. Sadly, history shows that investors really can be their own worst enemies and are much more prone to buying high and selling low. The flip side is that for the most part, the longer you stay invested, the greater the chance you’ll make gains.

Act like an owner

The best advice for reconciling share price with business value is to treat your investment in a public company as if you’re buying the entire business. If you can’t do that, find someone who will on your behalf. Acting like a business owner alleviates the worry around the larger economy or the market as a whole and gives you the deep perspective you need to make smart decisions. While far from easy to gain proficiency in – we’ve focused our entire adult life on it and still learn something new every day – understanding how to properly value a business and taking the right psychological approach to stock prices are really the only requirements to becoming a successful investor.

††Source: Bloomberg LP. Annual adjusted earnings per share and stock price in C$. Decline in stock price does not include reinvestment of dividends. 34% decline:12/10/2007 – 11/20/2008; 20% decline: 01/02/2009 – 05/22/2009; 12% decline: 05/10/2011– 08/08/2011; 22% decline: 05/07/2012 – 12/04/2012. Stock price as at December 12, 2014. Q4 2014 EPS estimate source: FactSet Research Systems Inc.

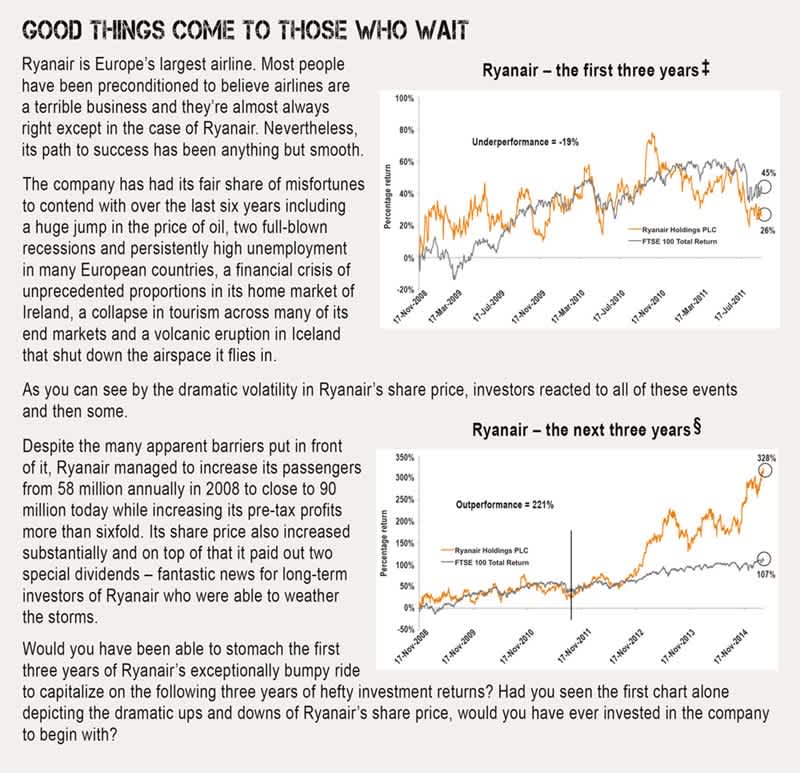

‡Source: Bloomberg LP. November 17, 2008 to September 17, 2011. In GBP.

§Source: Bloomberg LP. November 17, 2008 to March 31, 2015. In GBP.