If you happened to blink, you might have missed it, but the market experienced a pretty steep drop in the first quarter of 2020. Since then, the economy’s come a long way in trying to reopen and shutdown, only to reopen and shutdown again. Now the world seems on the brink of recovery with the breakthrough that is the long-awaited COVID-19 vaccine.

Considering the widespread lockdowns, travel restrictions, consumer trepidation and plunging business confidence, there’s little doubt that the market rebound we’ve experienced owes itself in large part to the previously inconceivable levels of government spending and central bank support.

Debt + debt = more debt

For Canadians, from the perspective of our national debt, navigating our way through the pandemic has been a pricey endeavour.

Increase in debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios for mature markets

Dec. 31, 2019 to Sep. 30, 2020

Source: Heaven, Pamela. “Posthaste: Canada is leading the ‘debt tsunami’ now sweeping the world”. Financial Post, November 19, 2020. https://financialpost.com/executive/executive-summary/posthaste-canada-is-leading-the-debt-tsunami-now-sweeping-the-world.

Non-fin. Corporates refers to non-financial corporates.

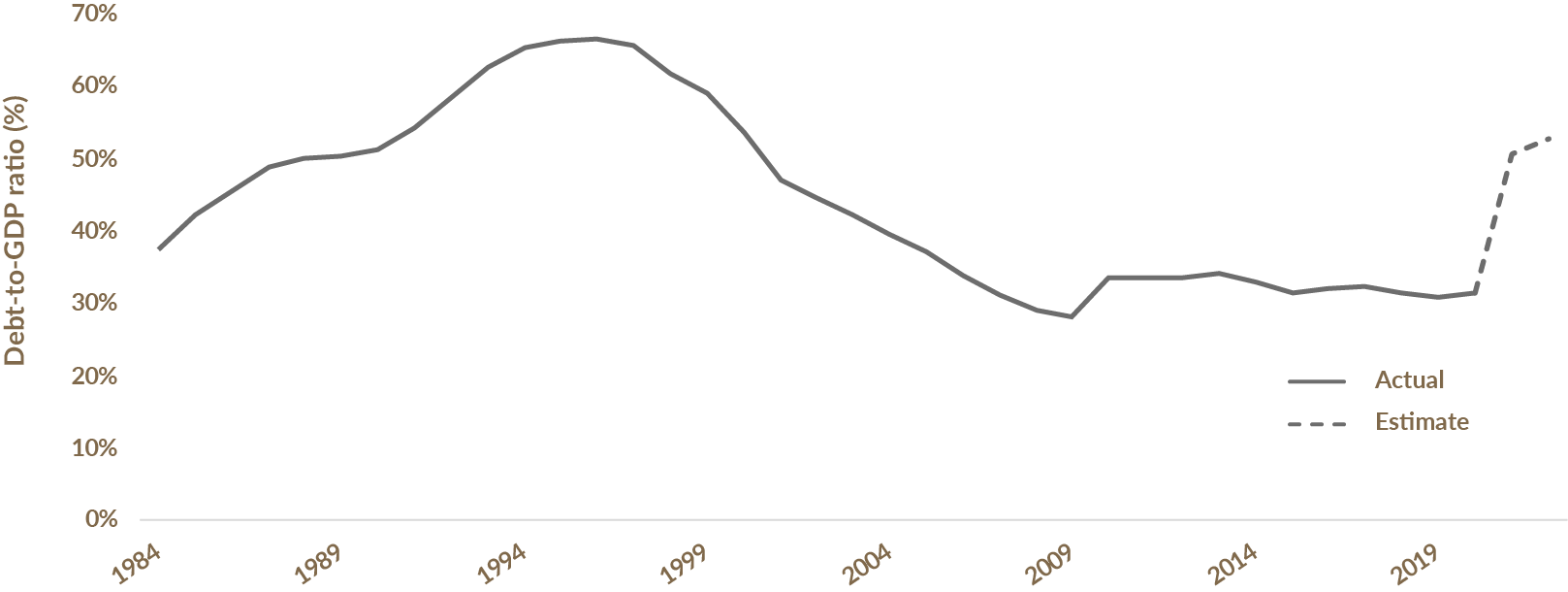

Given a forecast Canadian federal deficit of $381.6 billion, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio will rise to 50.7% by the end of the fiscal year ending March 2021. Not to stop there, a full $121.2 billion in added deficit spending is pencilled in for the “2021-22 budget” bringing the forecast federal debt-to-GDP to 52.6% by March 2022.i

Canadian federal government debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP)

Dec. 31, 1984 to Dec. 31, 2022*

*2021 and 2022 debt-to-GDP values are estimates.

Source: Canada. Department of Finance Canada. Fiscal Reference Tables 2020. Canada, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/services/publications/fiscal-reference-tables/2020.html.

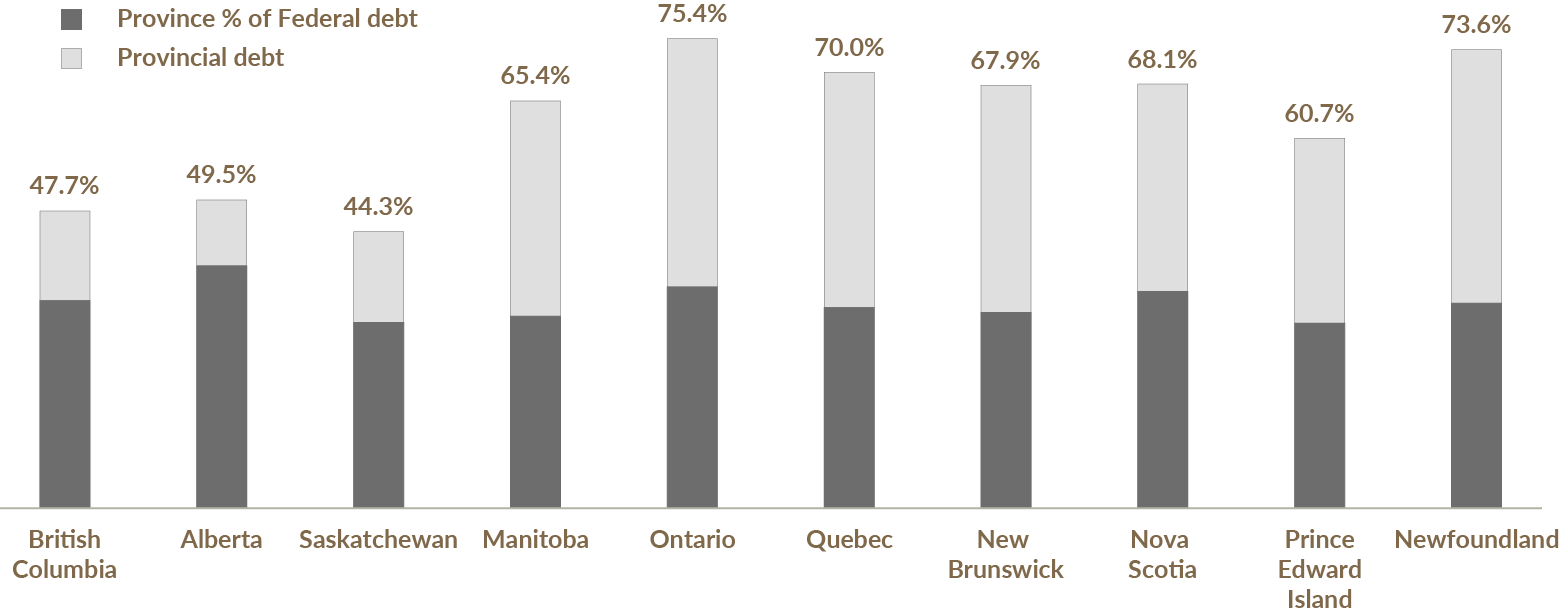

Of course, the government debt burden of the average Canadian does not stop at the federal level. In Canada, provinces bear the brunt of the larger public spending programs (like healthcare and education) and incur the debt to fund these outlays. Canada’s federal debt is only half the picture. The trajectory of Ontario’s financial position is shown below.

Ontario net debt-to-GDP ratio

1990 to 2023*

*2021 to 2023 debt-to-GDP values are estimates.

Source: Canada. Ontario. Government of Ontario. Ontario’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook in Brief. Ontario, 2020. https://budget.ontario.ca/2020/brief.html#c0-5.

And it’s not just Ontario. Each and every province owes the two layers of debt that fund federal and provincial spending. Adjusting for these balances, Canadians entered 2020 as financially stretched as most heavily indebted nations. Combining the projected increases, debt-to-GDP for the average Ontarian will rise toward 105% (50.7% + 52.6%) by March 2022.

Combined provincial and federal debt-to-GDP ratio by province

As at December 31, 2019 (pre-COVID-19)

Source: Fuss, Jake & Palacios, Milagros. The Growing Debt Burden for Canadians. The Fraser Institute. January 2020. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/growing-debt-burden-for-canadians.pdf. As at December 31, 2019.

We are entering newfound territory in the amount of borrowing assumed by our country, and it’s anyone’s guess how this plays out.

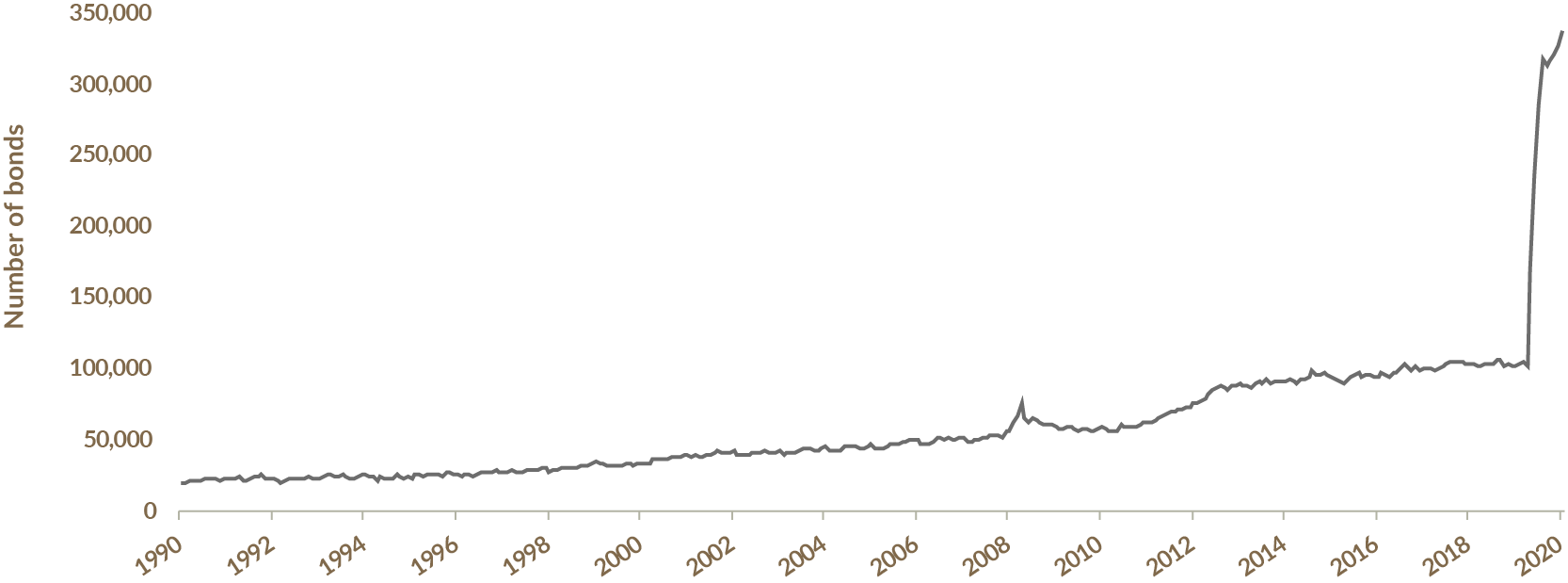

To borrow all this money, the Government of Canada issues bonds, and in 2020 by far the largest buyer of those bonds was our country’s central bank, the Bank of Canada. From January through to the end of November 2020, the Bank of Canada had purchased more than $225 billion of bonds issued by the federal government, and it now owns almost 35% of all bonds outstanding. Purchases continue to the tune of $4 billion per week.ii

Outstanding Government of Canada bonds held by the Bank of Canada

Dec. 31, 1990 to Dec. 31, 2020

Source: Bloomberg LP. As at December 31, 2020

But the Bank of Canada lending spree isn’t confined to direct purchases of Government of Canada bonds. To support markets in 2020, our central bank also purchased provincial bonds, Canadian mortgage bonds, money market funds and corporate bonds. More significantly, the Bank of Canada has been lending enormous sums of money to Canada’s largest financial institutions by taking “securities purchased under resale agreements” as collateral. Canada’s financial institutions then turn around and, for example, lend those proceeds to buyers of Toronto houses, or they themselves buy more Canadian government bonds.

Bank of Canada asset profile (C$B)

As at September 30, 2020

Source: Canada. Bank of Canada. 2020 Quarterly Financial Report. Canada, 2020. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/quarterly-financial-report-third-quarter_2020.pdf. Purchase and resale agreements are a form of collateralized financing where the buyer of the securities lends cash to the seller; this is the way the Bank of Canada lends money to commercial banks.

All told, the Bank of Canada has expanded its balance sheet (this is a euphemism for “printed money”) by more than $400 billion to fund the large deficits that we have seen this year. Assuming the bond purchase program continues at $4 billion per week through the end of March 2021, the roughly $475 billion in cumulative central bank support will almost exactly offset the federal borrowing needs for the 2020-21 fiscal year of $469 billion.iii If you were wondering what “Modern Monetary Theory” was, we are living it.

What happens now?

The situation laid out is by no means unique to Canada (although we do find ourselves at the top of the “more debt” list), and the point isn’t to argue the necessity of the spending or how we got here. But we must ask the question that nobody wants the answer to: what happens now? Nothing good, in our view. The debate today is split between two separate camps:

The debt burden caused by ballooning government deficits and the higher tax or lower spending that results will be a significant drag on economic activity and result in slower growth and deflation; or

The fact that we printed all the money needed to fund the deficits will result in rising inflation.

For anyone holding fixed income securities like long-term bonds, rising inflation would, in a nutshell, destroy investor wealth. But investors would be no better off lending money to a government with runaway deficits that is simultaneously grappling with deflation (imagine taking on a mortgage to buy a big house and then having your wages cut each year going forward). Central banks are likely to avoid deflation at all cost and would get more deliberate in their money printing before allowing declining prices (and declining tax revenue) to take hold. At this point, inflation may be the only way out.

Phoney interest rates and a false sense of security

With a central bank on pace to purchase the equivalent of 100% of all Government of Canada bond issuances this year, we can say with some level of certainty that market-observed interest rates are no longer representative of reality, and anyone buying them is in for a tough slog.

Not a single point on the Canadian yield curve today offers a positive return after accounting for inflation using any of the recorded readings of average core inflation over the past seven years. We believe buying bonds at these yields is a good way to run out of money before you die.

Source: Government of Canada Bond Yields; Bloomberg LP. As at December 31, 2020. Source, inflation: Scotiabank Economics, Statistics Canada. As at December 16, 2020.

Yield-to-maturity is the total return anticipated on a bond if it’s held until it matures and coupon payments are reinvested at the yield-to-maturity. Yield-to-maturity is expressed as an annual rate of return.

The elephant in the room is the risk that interest rates start to rise and the cost to carry all this debt begins to threaten the long-term finances of our country and the provinces. Needless to say, the record-low interest rates that accompany massive central bank bond buying have prolonged the “day of reckoning” for all significant borrowers by reducing the carrying costs of their debt. As governments and individuals surpass any previous record for amount of debt, it seems to be a growing consensus that “interest rates can’t go higher because it would decimate borrowers.” And they say millennials are utopic!

So, interest rates can’t move higher because our country can’t afford it. However, the notion that relentless deficit spending and money printing won’t be inflationary is impossible to imagine. Since they’ve gotten away with it so far, the world’s central banks seem to think there is no limit and no repercussion to their action. But the point isn’t to push it to the limit – we do not want to see the limit. We’re playing with fire and we are doused in kerosene.

Don’t be the lender to “lock in” historically low interest rates

In EdgePoint’s Growth & Income Portfolios, we can avoid the potential pain of rising interest rates and inflation by buying only short-term bonds, while waiting for a more realistic interest rate environment before committing capital for any term. Our unwillingness to own long-dated bonds has and will continue to mean that when interest rates decline in a meaningful way, our fixed income investments are likely to exhibit lagging performance over a short timeframe, compared to the benchmark or other investments that own long-term bonds. We experienced such an episode in the first quarter of 2020. But as interest rates decline toward zero, we are all-the-more incented to avoid long-term bonds. It is our view that the potential for rising inflation is the most mispriced risk in investment markets today. As a result, long-term bonds are loaded with more risk and less reward than at any time in history.

While we did not benefit from this year’s decline in interest rates, we found other opportunities by taking advantage of dislocations in the corporate bond market. The volatility exhibited earlier this year and the bifurcated markets that continue to this day have allowed us to make up a substantial portion of the shortfall that came from owning only short-term bonds, while protecting the portfolios from the risk of rising inflation and higher interest rates.

Just like we are fully unwilling to buy long-term government bonds at artificially low yields that are unlikely to deliver a return that exceeds even inflation, our government would sure like to sell them. If they can lock in phoney interest rates by selling 30-year bonds to unbeknownst investors outside of the central bank (e.g., mindless index funds), all the power to them. It can pay to have an active manager who will stay clear of such nonsense.

Source: Canada. Government of Canada. Debt Management Strategy for 2020-21, Annex 3. Canada, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/services/publications/economic-fiscal-snapshot/debt-management-strategy-2020-21.html.

Don’t be the patsy who buys those long bonds.

We’re not paid for what didn’t happen

Something that isn’t talked about enough in portfolio management are the risks that a portfolio is managed to handle. Unlike the precarious state of our country’s finances, we need to run our portfolios under the assumption that interest rates might move higher. We also need to assume that credit markets could tighten, companies’ access to financing could dry up, valuations might matter and the “animal spirits” that dominate today’s credit markets could dissipate. If any of this happens, our investment approach relies on an often-forgotten consideration in security selection: company fundamentals.

What investors endured in March 2020 was no ordinary correction. Look as far back as the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting in early May to see Warren Buffett – likely the greatest investor of our time – suggest there were times in the first quarter where it felt like $120 billion in dry-powder wasn’t enough cash! In times of little-to-no liquidity, company fundamentals come screaming to the fore.

Record monetary stimulus and government fiscal spending had some positive impact on market performance. But if we had not gotten them, we still needed a portfolio that could survive – and thrive. Shown below is a slide introduced in June 2020 originally meant to highlight how our portfolio of smaller, misunderstood and unrated bonds was not experiencing the rapid rebound of larger, liquid, widely followed names. By the end of May, the dust had settled and the market was no longer on fire, but recovery and any certainty surrounding the ultimate impact of COVID-19 was still a long way off.

The market collapse in early 2020 was an incredible opportunity, but that does not mean we bet the farm on rapid COVID recovery. With uncertainty at the fore, our focus was on buying the mispriced bonds of businesses that we had conviction could withstand the pandemic and economic shutdown regardless of how long the circumstances endured, yet still offered exceptional returns. By no means is this a perfect measure, but to illustrate the COVID-resilience of the businesses we were buying, we include the performance of each company’s stock through the full calendar year 2020.

| Examples of high-yield fixed income holdings in our portfolios | Bond rating | Issue size ($M) | Yield-to-worst | Calendar-year 2020 equity total return |

|---|

Source: Bloomberg LP. Bond rating and yield-to-worst as at May 31, 2020. Issue size of each bond measured in local currency. Calendar-year 2020 equity total return measured in local currency. Standard & Poor’s (S&P) credit ratings were used above for bond ratings. Yield-to-worst is a measure of the lowest possible yield an investor would receive for a bond that may have call provisions, allowing the issuer to close it out before the maturity date. Calendar-year 2020 equity total return is the calendar-year return for the underlying equity securities for the above bonds. All high-yield securities listed above were held in EdgePoint Global Growth & Income Portfolio or EdgePoint Canadian Growth & Income Portfolio.

Hindsight is 20/20, and after watching how strongly the securities of COVID-impacted businesses have responded (owing more to central bank support and U.S. Federal Reserve action than anything fundamental to most businesses), it is possible that we were giving too wide a berth to the lasting impact of the pandemic on many companies. As things stand, the now famous Barstool Sports Presidenté David “Davey Day Trader” Portnoy portfolio blindly buying airlines, cruise ships, rental cars, and the suppliers selling into these businesses was the right move if we wanted to make a lot more money. But it wasn’t the prudent move.

Howard Marks, Chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, often talks about the six-foot-tall man who drowned crossing the stream that was five feet deep on average. There are bad days in markets, and on the days that have no liquidity, no dilutive equity raises, no government backstop and no patsy investors awash in cash to offload your investments to, you still need to get your money back. It is important to reiterate, while our high-yield portfolio experienced meaningful downside volatility through the first three months of 2020, it is our belief that at no time were our businesses at risk of suffering permanent impairment to their enterprise. We will never jeopardize meaningful loss for potential return.

The collapse in junk bond prices at the start of 2020 was the second-worst drawdown in high yield history. There is no reason to expect that such episodes of volatility will be more common in the future than they have been in the past, but when we get them, such periods should be treated as a gift to anyone looking to maximize future returns. If there’s any clear takeaway from the past 12 months, it’s that high-yield bonds remain one of the best ways to capitalize on chaotic markets and deploy capital at attractive rates while protecting from permanent loss under even the most extreme adverse scenarios.

| Decline period (peak-to-trough) | % Decline | # of days (peak-to-trough) | 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years |

|---|

Source: Bloomberg LP. Total returns in US$. The ICE BofAML US High Yield Index tracks the performance of high-yield corporate debt denominated in US$ and publicly issued in the U.S. domestic market.

† The early 1990s U.S. commercial real estate crash is attributed to the failure of savings & loan institutions in the late 1980s to early 1990s due to inflation of those properties. Source: Geltner, David, “Commercial Real Estate and the 1990-91 Recession in the United States”, Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Department of Urban Studies &Planning, MIT Center for Real Estate, January 2013. https://mitcre.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Commercial_Real_Estate_and_the_1990-91_Recession_in_the_US.pdf.

More recently, as markets have recovered, medical professionals have a better understanding of the severity of COVID-19, the population has adapted to living with the virus and vaccines are being deployed around the world, markets are starting to envision life beyond the pandemic. But while many businesses are experiencing only temporary disruption, others could see permanent impairment. Despite the rebound in the stocks and bonds of many pandemic-impacted businesses, longer-term issues and challenges remain:

Office space could see lower demand as senior executives realize the benefits of working from home, and look to rationalize office footprint to cut cost and operate more efficiently

Business air travel that made up 80% of pre-pandemic revenue may return only at a slow pace, impacting both airlines and the car rental companies that depend on these customers

Cruise lines could experience a prolonged period of oversupply as pre-ordered ships continue to be delivered, and as stretched balance sheets lead to intense price competition

With any decline in even medium-term travel demand, aircraft manufacturers could reduce build-rates on new aircraft, changing the profitability profile for suppliers on many aircraft programs

Bumpy road to long-term outperformance

Not all of our businesses were immune to the impact of COVID-19. The table with high-yield securities shown earlier includes a bond of an energy services business (Tervita) whose stock remains priced as if oil was still trading at the unprecedented -US$35 per barrel we saw back in April 2020. But relative to most energy services companies, this business has uniquely wide margins, low fixed costs and low sustaining capital requirements, and proved resilient in 2020.

Similar businesses related to oil and gas that we thought were priced to offer outsized returns at the start of 2020 are all-the-more enticing today.

We had a small default when Hertz, the car rental company, failed to make a payment on its vehicle financing and filed for bankruptcy to restructure its debt, but we still had a positive holding period return on this bond.iv Along the same lines, we bought and subsequently sold the bonds of Air Canada early in the pandemic. While it is important to be aggressive in times of market turmoil, in each case we struggled to answer questions about the long-term earnings power of these businesses, and felt it was irresponsible to retain the positions. Time will tell whether these companies are successful on the other side of COVID-19. In our view, neither is out of the woods despite the strong rebound in the prices of their bonds.

With vaccination, visibility on a path forward and a better understanding of how shutdowns impact the cash flow profiles of different businesses, we have recently invested in discounted bonds of companies that have been more impacted by COVID-19, but at the same time should easily manage if current conditions persist. We believe each of the following bonds were priced to offer near double-digit returns at time of investment. For example:

Dave & Buster’s operates a chain of highly profitable restaurants that combine food and amusement games whose venues have returned to 90% of 2019 sales levels in reopened regions

In a U.S. market that may well see a reduction in the number of cinemas, Cinemark’s strong balance sheet and prudent management team is uniquely positioned to benefit from struggling competitors

We’ve initiated a position in a company distained by the market as a result of its (still lucrative) coal-royalty portfolio, but whose equity stake in an unrelated business may, in our view, be worth the value of the company’s debt, and whose bonds are priced to yield 11.5%

The strong returns since the depths of March cannot go on forever, and we are not immune to a world of low interest rates and tight credit spreads. But our portfolio is not the market. Looking back on 2020, it’s interesting to think that we’ve earned a satisfactorily positive fixed income return despite having endured the greatest pandemic of the past 100 years, all while being left with a more attractive portfolio on the other side. And as much as it is our job to add value by protecting the portfolio in tough times, we similarly expect to add value when returns are scarce, by prudently managing risk and continuing to look where others aren’t looking.

ii Hagan, Shelly. “Bank of Canada to Restate Low-Rate Guidance: Decision-Day Guide “. Bloomberg.com, December 9, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-12-08/bank-of-canada-to-restate-low-rate-guidance-decision-day-guide

iii Canada. Government of Canada. Debt Management Strategy for 2020-21, Annex 3. Canada, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/services/publications/economic-fiscal-snapshot/debt-management-strategy-2020-21.html

iv Hertz Corp. 7.625% 01-jun-2022 bond was held in both EdgePoint Growth & Income Portfolios from August 2017 to July 2020. Performance calculated in C$.