The most important question – 4th quarter 2015

Why are you reading this commentary? Your time is very valuable and we appreciate you spending some of it reading about your EdgePoint investment. If we had to guess, the number one reason you’re reading this is to gain some insight into the following question:

Will my EdgePoint investment deliver pleasing returns in the future?

The word “pleasing” is very qualitative and subjective. It can mean different things to different people so we’re going to try to quantify it a bit in an effort to make the question a little more meaningful.

Inflation erodes the value of your money every day. In fact, at a 3% inflation rate, the value of your money halves every 23 years. That bag of groceries you bought yesterday will cost you twice as much in 23 years, three times as much in 37 years and four times as much in 46 years. Essentially, a forty-year-old investor will have to pay four times as much for the lifestyle they enjoy today when they’re 86. So at a minimum, most people would define “pleasing” as having an ability to deliver a rate of return equivalent to inflation over the long term. If inflation is in fact 3% annually and your investments deliver less than that, then you’re slowly going broke. It’s safe to assume that everyone would agree that slowly going broke is NOT “pleasing”.

At the other end of the “pleasing” spectrum might be the since inception returns of our portfolios. Whenever we mention historical returns, we’re legally obligated to show you the following table, so here are the since inception returns highlighted:

| Portfolio | 1-Year | 3-Year | 5-Year | Since Inception* |

|---|

You’re among over 120,000 families invested in EdgePoint portfolios and many of you have been invested with us for years. Based on this continued support, we assume you’re “pleased” with your longer-term performance. Though in our view, that historical performance we showed above marked the high-end of the “pleasing” spectrum simply because the opportunities available to investors when we started EdgePoint in 2008 aren’t the same as what’s available today.

Specifically, in 2008 the stock market was consumed with fear so businesses were trading at extremely low valuations. While fear still exists in pockets of the market today, it’s much less prevalent than it was back in 2008. It may be perceived as counterintuitive, but at EdgePoint we believe money is made when you buy an investment and not when it’s sold. Most are conditioned to feel like they’ve made money when an asset is sold and they receive cash for it. We believe money is actually made when the asset is purchased for less than it’s worth. When we started in 2008, there were just more businesses trading at big discounts than today, so we believe the high-end of “pleasing” should be the since inception returns of our portfolios.

Bearing all this in mind, we should rephrase our question from above and ask:

Will my EdgePoint investment deliver returns somewhere between the rate of inflation and the historical returns delivered by the portfolios?

In an effort to answer that question, let’s first look at what investors are worried about because it has the potential to impact returns, or does it? One of the things that has loomed large on the minds of investors is the ultra-low interest rate environment.

When the financial credit crisis initially broke in 2007, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates hoping to increase aggregate demand. When it wasn’t successful (largely because consumers had already taken on large amounts of debt and weren’t in a position to increase their spending), the Fed decided to increase money supply. The increase in supply was the quantitative easing you’ve been hearing about. It printed money and used that money to buy assets thinking that if the lower rates weren’t enough to cause asset prices to rise, this would surely do the trick. It makes a person feel richer by increasing the prices of their assets, which in turn makes them feel comfortable increasing their spending. While the U.S. has pulled back its quantitative easing, it’s still happening in Europe and Japan. Of course this supply (or we’d call it manufactured demand for assets) coupled with ultra-low interest rates contribute to the universal rise of asset prices. Great news for those with lots of assets – unless of course it’s cash. It has become the one consistent waning asset, earning near 0% in this ultra-low interest rate paradigm. It’s a waning asset because it doesn’t earn enough to match the inflation of other assets, products or services.

What if interest rates stay low?

It’s important to pay attention to interest rates because most people value assets at the time of purchase based on prevailing interest rates. The lower the rate, the more debt you can carry and thus “afford” more assets. It also causes future cash flows to appear more valuable to those who think rates will remain low. Low rates make lenders think they’re smarter than they really are since they’re able to lend more than if rates were high but with fewer defaults. They also assist, though only temporarily, the over-indebted and hurt the conservative saver. It helps the over-indebted because they can borrow more, consume more and still keep their head above water because interest rates are so low. It hurts the conservative saver because their interest income either doesn’t match inflation or they experience capital losses reaching for higher yield. Historically, the saver had a simple option to derive income from cash. Today, it isn’t as simple. Investors who in the past yielded income from cash are now forced to invest in “opportunities” offered by promoters who promise yield. And guess what, these opportunities conveniently “offer” the very yield the investor requires. It’s amazing how that happens. Unfortunately, in order to achieve the yield they want, there’s often an increase in risk – though this is rarely pointed out to investors and pain ensues for the conservative saver. Let’s do a reality check. Rates wouldn’t be this low and the central banks wouldn’t be printing money if everything was rosy in the world.

Does it matter, or is it just the reality of the world we live in?

What doesn’t matter?

Does it matter if central bankers’ monetary experiment continues for another 10 years? Should you care if it does? Does it matter that central bank policy benefits the 1%? Does it matter that printing money is contributing to cash becoming a waning asset? Are elevated asset prices and anemic GDP growth the new normal? Does it matter that a university education is becoming more and more unaffordable each year for the average family? Does it matter that average middle-income salaries haven’t kept up with the inflation central bankers claim doesn’t exist? Does it matter if the average person can’t afford the average house? Does it matter that central banks have sponsored interest rates and excess capital-induced bull markets…and bubbles? Does it matter that governments won’t live up to their future promises even with major tax increases? If the middle class is already falling behind, where will the tax increase come from?

Of course all these things matter but this is the reality of the world we live in even though it isn’t ideal on all fronts. Just because we don’t like it, we can’t change it and a lot of it might make us scratch our heads or fear that things could get worse. Doesn’t mean we can’t invest in it. And it certainly doesn’t mean we can’t prosper in it. But not all will prosper for sure.

What does matter?

With the task at hand to grow wealth overtime, let’s talk about what we think matters. The most important factor in determining future returns is not any of the factors above. The most important thing is whether or not the market will give us opportunities to find proprietary views on businesses in an environment where capitalism carries the day.

Let’s re-visit the question we posed at the beginning of the commentary:

Will my EdgePoint investment deliver returns somewhere between the rate of inflation and the historical returns delivered by the portfolios? We believe the answer to that question is yes and that they should fall in that range over a meaningful amount of time.

Why do we believe this? We try to ensure that the businesses you own are run by competent managers, that they don’t have too much debt and have material economic moats around them. Beyond these obvious things are two other factors in particular that give us confidence that we’ll be able to deliver “pleasing” returns in the future:

Proprietary insights

Volatility

Proprietary insights

We believe the best way to buy a business at an attractive price is to have an idea about the business that isn't widely shared by others – what we refer to as a proprietary insight.

We strive to develop proprietary insights around businesses we understand. They generally reflect our views looking out more than five years. We firmly believe that focusing on longer periods enables us to develop proprietary views that aren't reflected in the current stock price.

The foundation of a proprietary insight is to be long-term investors in businesses. We view a stock as an ownership interest in a company and endeavour to acquire these ownership stakes at prices below our assessment of their true worth.

Volatility

What gives us the ability to buy a business below its true worth is volatility. We like to capitalize on volatility as much as possible.

As many of our investment partners already know, we believe volatility is the friend of the investor who knows the value of a business and the enemy of the investor who doesn’t. Volatility is caused by emotions. The two primary emotions that drive volatility are greed and fear. Here’s a walk down memory lane of a few emotional drivers from the past few years. Remember when we saw these headlines?

U.S. housing was doomed forever so most investors shied away from businesses whose prospects depended on new home construction returning to trend

U.S. unemployment was going to remain structurally high forever so investors steered clear of businesses associated with employment levels improving

The BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China) were going to drive the price of oil to US$200 a barrel and airlines were doomed because of it

The U.S. dollar was going to collapse so U.S. businesses fell out of favour with investors

Obamacare was going to destroy health insurance companies

More recently, here are the fears 2015 will likely be remembered for:

Oil collapsed from US$120 to US$35 per barrel and consensus was it would never go up again

BRIC demand collapsed and caused a recession in industrial demand so no one wanted to buy an industrial-related company

Interest rates started to rise so people became worried about the U.S. housing market

People worried about a permanent shift down in global transportation demand

Over the past few years, we bought and/or added to businesses impacted by each of these fears. However, we don’t buy businesses just because they fall out of favour. We try to take advantage of irrational price movements in great businesses caused by short-term noise. This is what we did in EdgePoint Global during each one of those periods mentioned above.

When the Fed was never going to raise interest rates and the last thing you wanted to own was a U.S. bank because of that.

We bought two U.S. banks with overcapitalized balance sheets, great management teams and lots of opportunity to take market share from their competitors

Source: Bloomberg, LP. Cumulative total return of the stock since date of purchase.

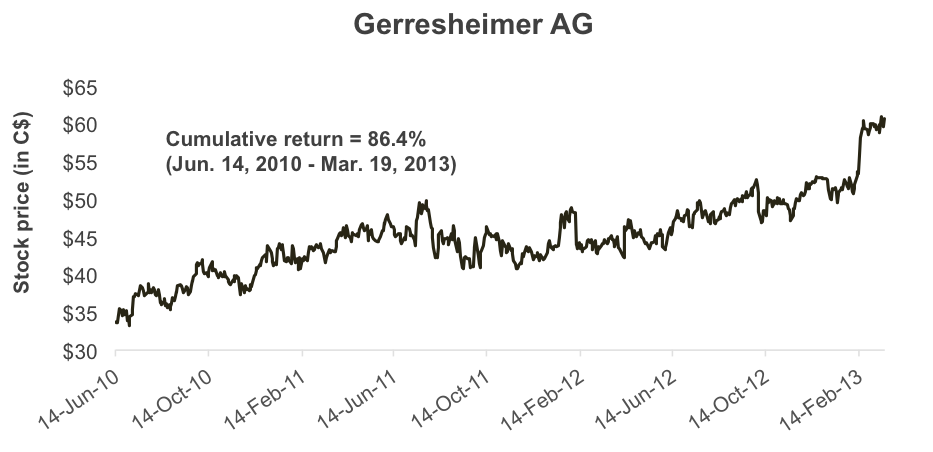

When Greece was going to cause a European collapse in 2010 and the last thing you wanted to own was a European business because of that.

We bought two German businesses that had virtually no exposure to Greece. Both had products that could grow in demand even if European GDP slowed, but both companies saw their share prices get cut dramatically because no one wanted to own anything in Europe

Source: Bloomberg, LP. Cumulative total return of the stock for holding period.

When U.S. housing was doomed forever and the last thing you wanted to own was a business based on the idea of new home construction returning to trend.

We believed that the U.S. would continue to build more homes to accommodate their population growth and bought a cabinet and faucet company

Source: Bloomberg, LP. Cumulative total return of the stock for holding period.

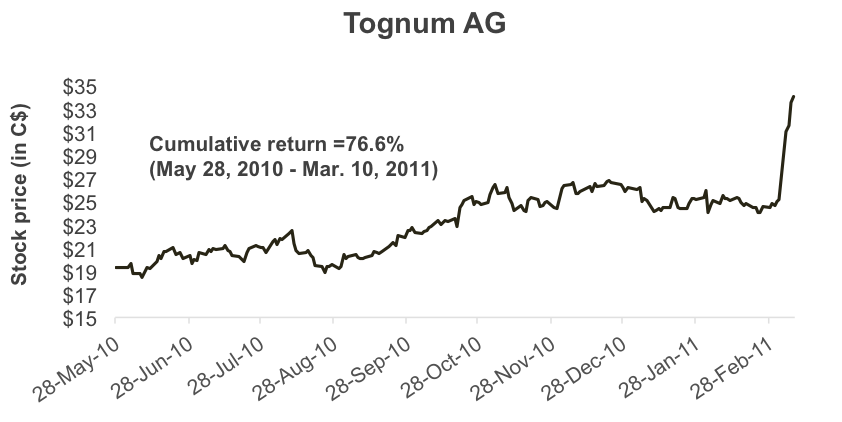

When U.S. unemployment was going to remain structurally high forever and you didn’t want to touch a business associated with employment levels improving.

We saw a nursing shortage in the making and bought a travel nurse company

Source: Bloomberg, LP. Cumulative total return of the stock for holding period.

When the BRICs were going to drive the price of oil to $200 a barrel and airlines were doomed because of it?

We bought an airline whose cost structure was approximately 50% lower than its closest competitors. This airline had no debt and was experiencing large growth in demand

Source: Bloomberg, LP. Cumulative total return of the stock for holding period.

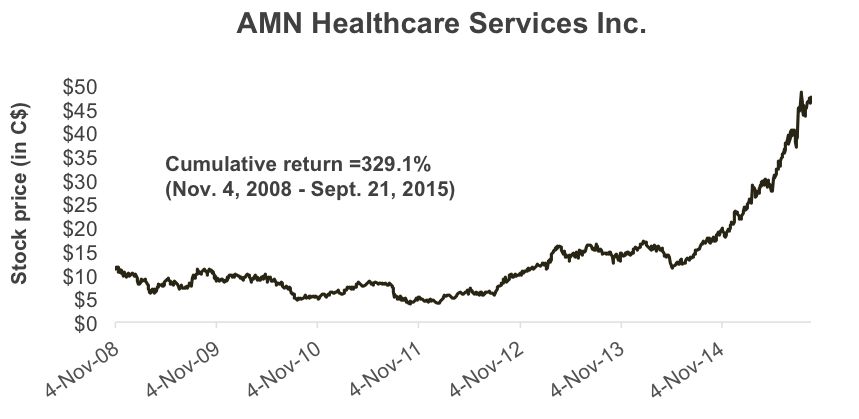

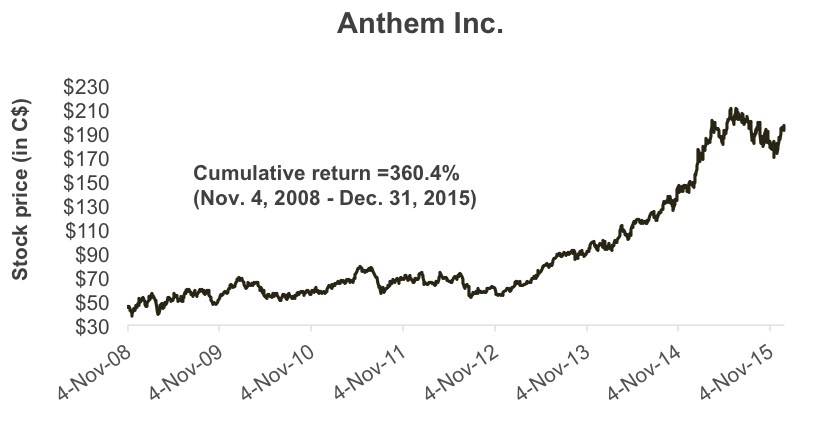

When Obamacare was going to destroy health insurance companies.

We bought the health insurance company with the greatest scale and the lowest cost structure. We believed it would be the last man standing if Obamacare was as bad as everyone feared it would be

Source: Bloomberg, LP. Cumulative total return of the stock since date of purchase.

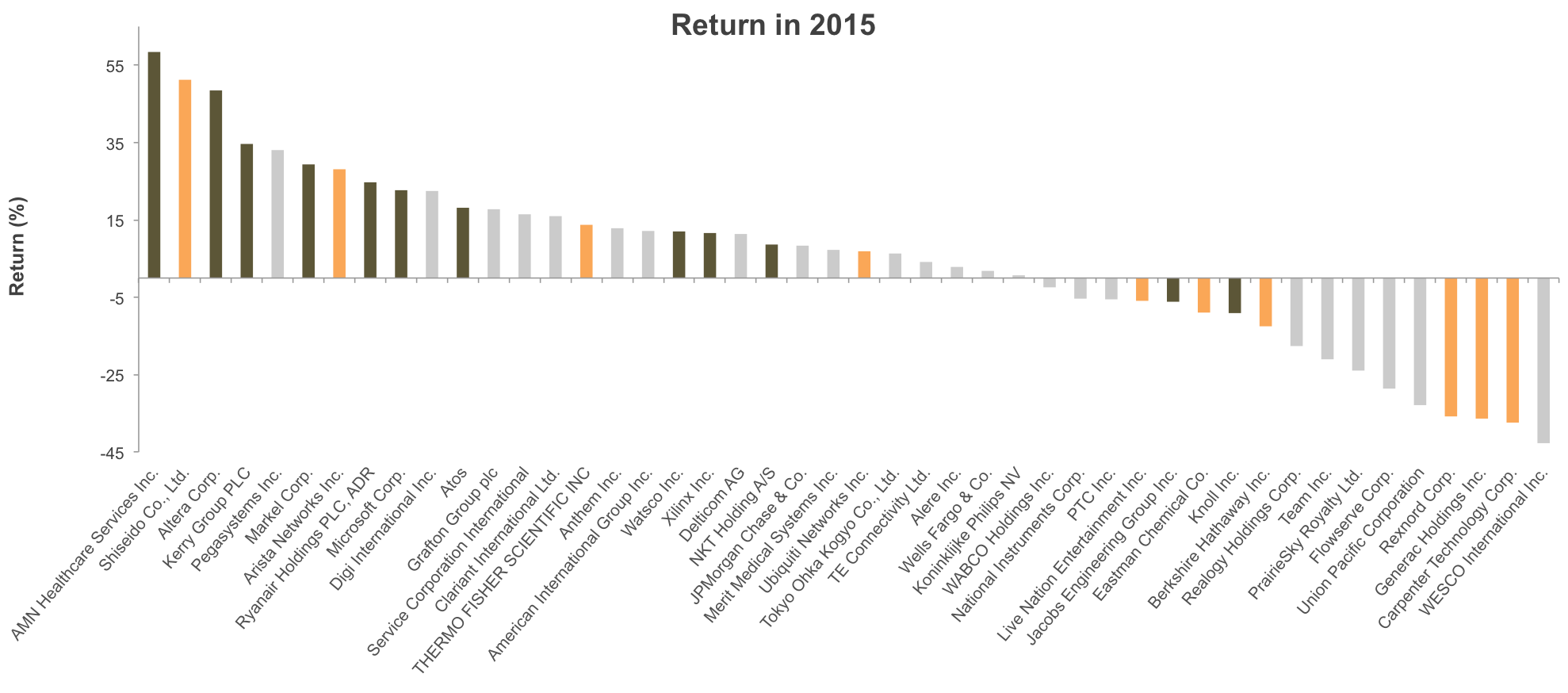

The following graph illustrates the annual percentage return for each one of the holdings in the EdgePoint Global Portfolio in 2015. The orange bars represent new ideas purchased during the year and the brown bars show names we sold during the year.

Return in 2015

Annualized total returns, net of fees, in C$ as at December 31, 2015

EdgePoint Global Portfolio, Series A - YTD: 12.71%; 1-year: 12.71%; 3-year: 24.60%; 5-year: 15.90%; since inception (Nov. 17, 2008): 17.73%.

Source: Bloomberg, LP. Annual returns in local currency. One holding was excluded as only partial returns available.

The key point that jumps out of the chart above is the vast disparity in returns of the individual names within the portfolio. In 2015, the market fell in love with companies like AMN Healthcare because the nursing shortage became obvious to everyone. And the drop in the oil price caused Ryanair’s profitability to balloon, and the market couldn’t get enough of its story. We sold our positions in both companies entirely while taking the weight down in other names on the left-hand side of the chart. We redeployed the proceeds into new and existing ideas on the right-hand side of the chart.

You may be wondering what type of companies were bought on the right-hand side of the chart? They were ones being impacted by the fears of day that 2015 will likely be remembered for.

Looking forward, what may cause us to under-deliver on the expected range of returns that we outlined previously?

While there are lots of macro-related fears like deflation or a prolonged depression in markets like China, history has proven that over a material amount of time these macro fears are transitory. Through world wars, epidemics, hyperinflation, depressions, and everything in between, investing in a sound collection of growing businesses has proven to be profitable. So the real threat to our ability to deliver “pleasing” returns going forward is our ability to execute our approach.

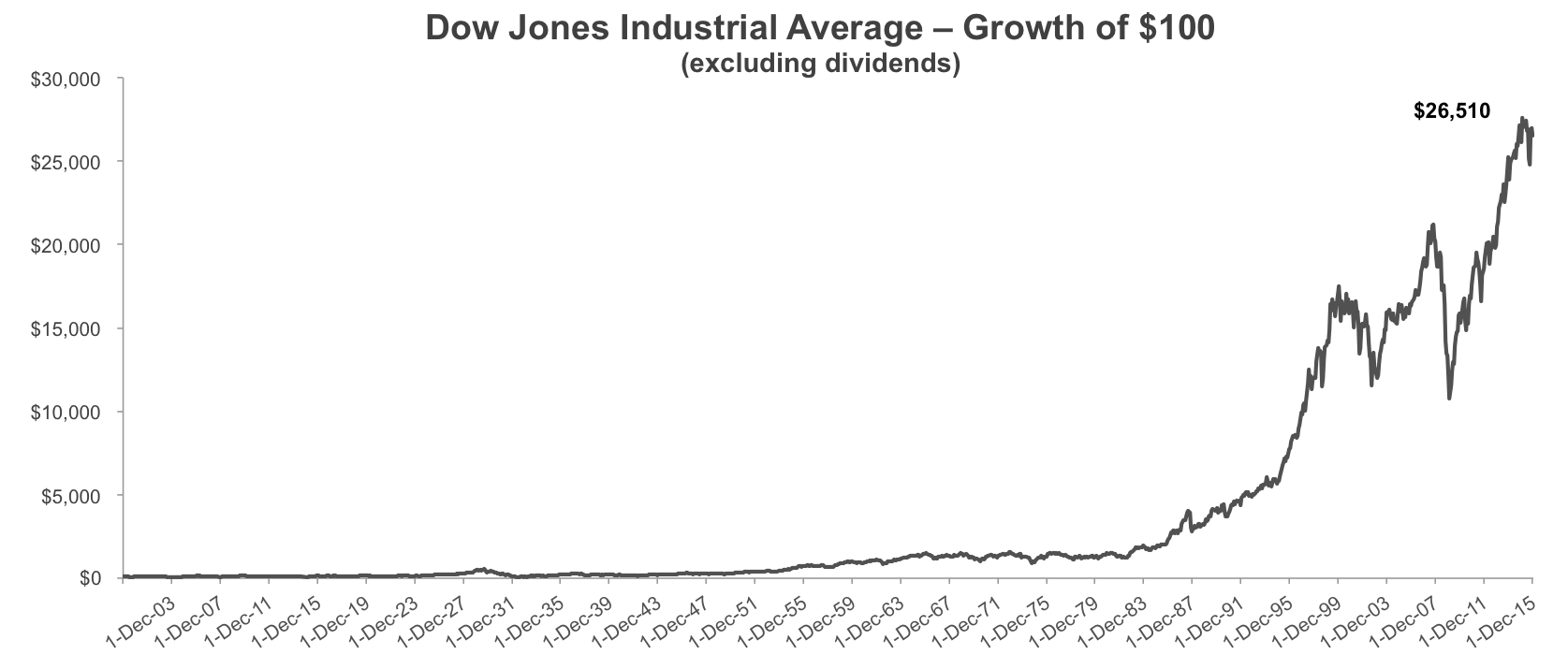

There have been big declines every decade to scare investors, but the gains from each decade far outpaced the drawdowns:

| Decade | Maximum Gain | Maximum Drawdown | Maximum Gain | # of Months | Maximum Loss | # of Months |

|---|

When you combine all of this data, $100 invested in the Dow Jones Industrial Average index at the beginning of 1900 would have grown to $26,510 today, not including dividends.

Source : Bloomberg, LP.

Historically, capitalism has worked and historically our investment approach has managed to outperform over material amounts of time. Our biggest threat isn’t the noise and fears we’ve discussed but how many mistakes we make as investors.

We’ve made some doozies in the past eight years. Since inception, we held and sold the following eight stocks in the EdgePoint Global Portfolio and each lost money:

Security

Connaught Plc

Research In Motion Ltd.

Bank of New York Mellon Corp.

Western Union Co.

Takata Corp.

GameStop Corp. - Class A

Jacobs Engineering Group Inc.

Cisco Systems Inc.

Fortunately, we’ve been well-diversified so the above mistakes were more than offset by the winners which resulted in material outperformance over time. We’re not promising to always pick winners but we continue to search for and invest behind our proprietary insights. Our portfolios are filled with unique insights that we believe will build value for you over time. Getting back to your original question, if we stick to our investment approach, accept that we’ll make mistakes but try to structure the portfolios in such a way that our winners more than offset our losers, we believe your portfolio will continue to deliver "pleasing" returns.

It’s best to accept the reality of the world for what it has become. You can choose to ignore or accept the things you don’t like or that might scare you about the future. Once you accept them, you need to develop an investment plan that aims to avoid any big problems down the road and grow enough wealth over time. The volatility that we expect to continue in the future should continue to help us find proprietary views. A good business that can grow, that is purchased at a price below our assessment of its true worth has always paid off handsomely. There’s no reason to believe that will change. That’s what convinces us that the future will be bright, even though on the surface, there seems to be a lot to worry about.

We continue to approach investing in these markets with measured confidence, value your trust in us and look forward to working to build your wealth in an effort to be worthy of that trust.

Fixed-income comments

By Frank Mullen, portfolio manager

Investors often hear quotes about the amount of fear and greed that exists in the market at any given time. In an effort to keep their viewers tuned in, the talking heads on television often make any move in the stock market sound like a remarkable event. While there are periods of extreme fear or greed in the market, there are also periods that are much more balanced. In general, balanced markets tend to be fairly priced, with fewer forced sellers to take advantage of and not many optimists to sell to.

We’d characterize the past several years in the fixed-income market as relatively balanced. There were certainly areas of the market that experienced short-term dislocations but in general we have remained in a low-rate environment with investors willing to pay more for securities that provide a yield. Bond prices have been bid upwards and yields pushed downwards to levels that weren’t overly attractive compared to other periods in history.

Those of you who’ve been following EdgePoint for several years know that we’ve been investing in a defensive nature in the fixed-income portion of the portfolios. We believe the past two years haven’t presented us the necessary opportunity set to invest aggressively. We felt the best way to maximize value was to be discerning and wait for the market to provide more attractive opportunities. To be clear, we managed to find many credit-specific investment ideas that provided pleasing returns over this time frame, but in general we didn’t feel the fixed-income market was overly attractive and as such maintained our defensive positioning. Patient opportunism is sometimes the best approach as the market doesn’t seek to provide high returns just because we all need them.

Two years ago the market presented us with the following:

| index | Yield-to-Maturity |

|---|

We don’t invest in broad asset classes. Rather we invest in individual securities based on fundamental credit analysis. That being said, looking at broad market data helps guide us to areas of the market that may be riper for opportunity than others.

In general, we felt corporate bonds provided the most attractive risk/reward, especially if we found individual credits whose balance sheets were improving and didn’t have the same default risk as the average borrower in the index. The key to our investment approach is always finding a proprietary insight that the market has not yet priced into the security. If we can buy a bond yielding 10% that we think is as credit worthy as others that only yield 8%, we not only earn a return from the coupon payments but also stand to benefit from capital appreciation if the market begins to think the same way we do.

Although we thought investment grade and high-yield debt were our best options, we didn’t think these investments were attractive enough for us to invest in them aggressively. We kept our fixed-income allocation at approximately 30% of our balanced portfolios, which is at the low end of the spectrum for us. We also made sure that we owned materially more investment grade bonds than high yield. Although the yield was relatively attractive at the time, we were concerned that the prolonged period of low interest rates was allowing less credit-worthy borrowers to refinance and survive despite the fact that their businesses were challenged and their debt levels too high.

Investing in government bonds wasn’t attractive to us as we didn’t think that the meager yields were compensating us for the interest rate risk that came with it. We aren’t macro forecasters but we did believe that at some point interest rates would rise, we just didn’t think we’d have to wait until the end of 2015 to see that occur. We’ll be watching how the market reacts to increasing yields.

The low-rate environment we’ve operated in since the crisis has caused many investors to reach for yield. When traditional safe investments fail to deliver a return in excess of most people’s inflation rate, it’s rational for investors seeking yield to turn to riskier investments. Taking on risk isn’t necessarily bad, but you must understand it and try to build a portfolio that isn’t overly exposed to a concentrated set of risks. Our since inception performance would have been better had we allocated the entire fixed-income portfolio to high-yield bonds but we wouldn’t have been comfortable with the risks that were inherent in making that decision.

Our investment approach frees us from the pressure to reach for yield. Most investors don’t share this luxury. They are burdened with the constant search for yield because they don’t want to underperform, even in the short term, as this could put their jobs at risk or cause anxious clients to withdraw their assets. We don’t feel the same pressure. We would prefer to outperform 100% of the time but we don’t think it’s possible. Short-term underperformance is generally required for long-term outperformance. Rather than swinging at every pitch, we prefer to wait until we see something in our strike zone that provides the potential for an attractive return while taking risks that we understand. We hope to attract clients who understand our process and are also patient with their capital.

Today the market is presenting us with a far different opportunity set than two years ago.

| index | Yield-to-Maturity |

|---|

The difference in yield on the U.S. high-yield index compared to investment grade/government bonds is striking with high-yield debt now yielding around 9%, as illustrated in the following chart.

Source: Bloomberg, LP. As at December 31, 2015. *Holds only investment grade bonds.

We’re beginning to place a greater emphasis on this area of the market hoping to identify individual businesses whose debt is selling off due to pressure in the overall market and not the fundamentals of the underlying businesses. The sharp increase in yields has occurred over a relatively short period of time. We don’t know if they’ll stay there, but we’re currently scouring the market for interesting opportunities in the high-yield space.

The portfolios are well positioned if the opportunities in high-yield bonds continue because we currently have the lowest allocation to the asset class since inception so there’s room to expand the allocation at any given time. The duration in both balanced portfolios continues to be less than three years which will give us plenty of dry powder to spend as our bonds mature and we redeploy into higher-yielding securities. Selling investment grade bonds to purchase high yield has the potential to be an attractive opportunity if we find the right investments. We continue to feel that equity markets are more attractive than fixed income which is why our allocation continues to favour equities at approximately 70%. Should valuations or relative opportunity sets change, we can shift this allocation to provide even more dry powder for attractive fixed-income opportunities.

It’s paramount that we continue to focus on the underlying business fundamentals of all new potential fixed-income investment ideas. Simply buying something because its price has fallen can have disastrous results. Fear is much more prevalent in the market today which is evident in the outflows we’re seeing in the high-yield market. Redemptions cause forced selling which can lead to lower prices even in businesses where the fundamentals remain strong. Price volatility driven by fear and not fundamentals should provide opportunities.

We don’t know what the future holds but I’m confident that current conditions are far more attractive than the ones we’ve been investing in over the past several years. The market has shifted from balanced to more fearful which should provide many more investment opportunities. We’ll strive to identify these and position the portfolios so we can gain from them.