The granny shot (or why you shouldn’t always listen to the crowd) – 4th quarter, 2020

The greatest game of basketball anyone ever played took place on March 2, 1962. Wilt Chamberlain of the Philadelphia Warriors scored 100 points in a single game. His whole 1961-1962 season was remarkable as he averaged more than 50 points a game. Both records remain intact five decades later and may never be broken.

So what happened that year? Chamberlain did something unusual – he decided to shoot his foul shots underhanded. It's often referred to as the "granny shot" because it looks like you’re shooting the way a granny would (no offence to grandmothers out there).

If you ask the experts, they will tell you that shooting underhanded is a better way to make foul shots. Your arms hang straight down, which is more natural, and your muscles don’t tense up. The granny shot has a larger margin of safety because the ball lands softer when it hits the rim, giving it a better chance of bouncing into the basket.

Philadelphia 76ers vs. Boston Celtics. Wilt Chamberlain, #13 of the Philadelphia 76ers, shooting a free throw underhanded.

During his first two seasons in the league, Chamberlain had the same issue that many seven-foot basketball players have – he was a terrible free throw shooter. In the greatest year of his career, he tried something unconventional. And it worked spectacularly.

The night Chamberlain scored 100 points, he made 28 out of 32 free throws (another record). Without the free throws, there would be no 100-point game.

But the story doesn’t end here. What do you think happened in the following season? Chamberlain stopped shooting underhanded and went back to being a terrible foul shooter.

If Chamberlain had shot the same free throw percentage every year of his career, he would have scored an extra 1,346 points.i Instead of being the seventh-highest scoring player of all time, he would have finished ahead of Michael Jordan.

Here’s the thing. Chamberlain had every incentive in the world to stick with his unconventional approach. He shattered scoring records using the granny shot. But the social pressure of standing out from the crowd was too much to handle. In his autobiography, Chamberlain wrote:

“I felt silly, like a sissy, shooting underhanded. I know I was wrong.

I know some of the best foul shooters in history shot that way…I just couldn’t do it.”Source: Gladwell, Malcolm. “The Big Man Can’t Shoot”. Revisionist History. Podcast transcript, July 6, 2017. https://blog.simonsays.ai/the-big-man-cant-shoot-with-malcolm-gladwell-e3-s1-revisionist-history-podcast-transcript-1b87d82c2546.

In case you’re wondering, of the hundreds of players in the NBA today, nobody uses the granny shot. The pressure to conform is real.

In this commentary, we’ll explore another deceptively simple (but effective) idea that’s difficult to do in practice – investing differently from everyone else.

Rules of the game

In the stock market, the collective view of the investing public is already reflected in the current price. In the short term, you might be able to make money investing without insight, but over time the stock market factors in common knowledge. Investing in Company X because it makes a great product or trades at a low multiple of earnings isn’t an insight if everybody knows the same information you do.

For example, let’s say you went to a grocery store and noticed a big lineup outside. Everyone in your neighbourhood is stockpiling sanitizers and toilet paper. Investing in the grocery store must be a good investment idea, right? The problem with this idea is that everybody else can see the same lineups outside their grocery stores. As a result, although it may seem compelling on the surface, this fact, would already be reflected in the stock price.

We believe investing is most successful when it is most business-like. Simply put, we look to invest in competitively advantaged businesses with long runways for growth and run by capable managers. Unfortunately, identifying a superior business isn’t enough to generate superior long-term returns. If you want to have an edge, you should only invest when you have an idea about a company that isn’t widely shared by others. We call this having a “proprietary insight.”

Returning to the grocery store example, you might have a view that COVID-19 will cause a permanent change in people’s preferences (e.g., even after the vaccine rollout, people will choose to eat at home more often). That would be considered a differentiated view that could lead to an attractive investment opportunity. But if you can’t explain what you know about a business that others don’t, you probably shouldn’t make the investment.

So if all it takes to succeed at investing is having a proprietary insight, then why doesn’t everyone do it?

Sticking to the game plan

Investing in a business when you have an idea that is different from others is deceptively simple. Easy to understand, but hard to execute in practice.

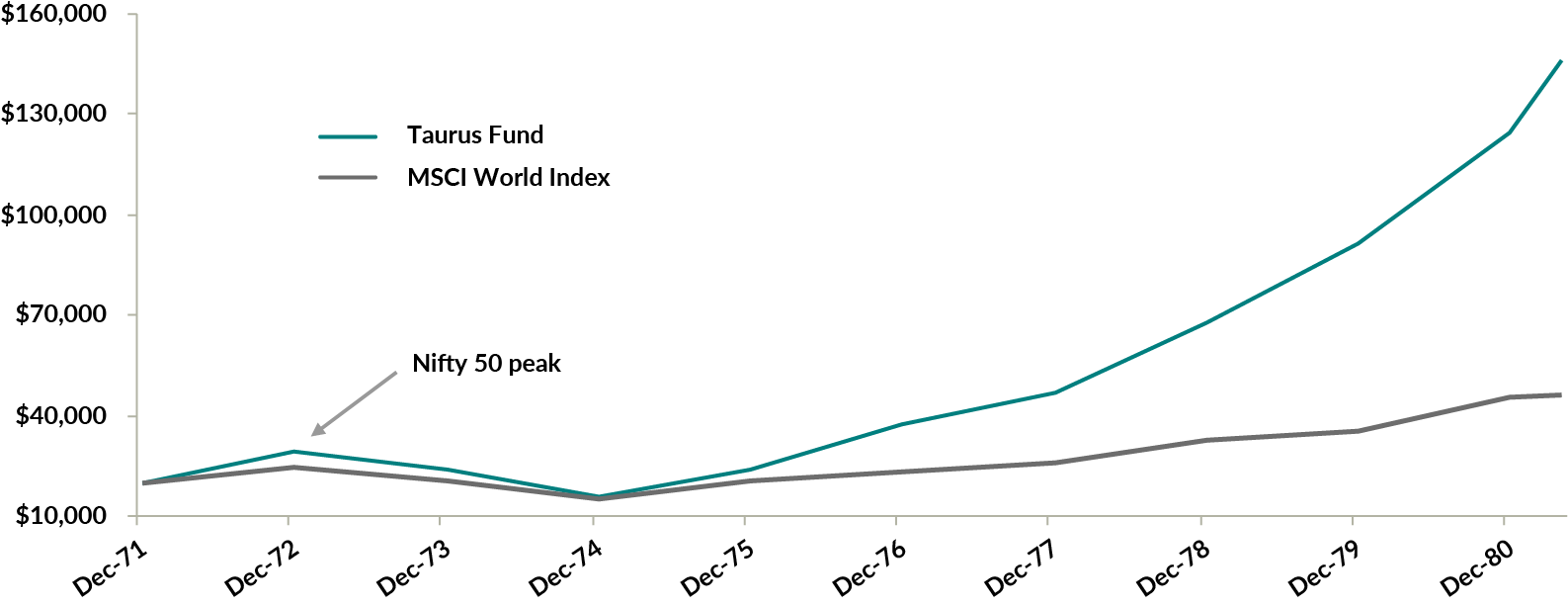

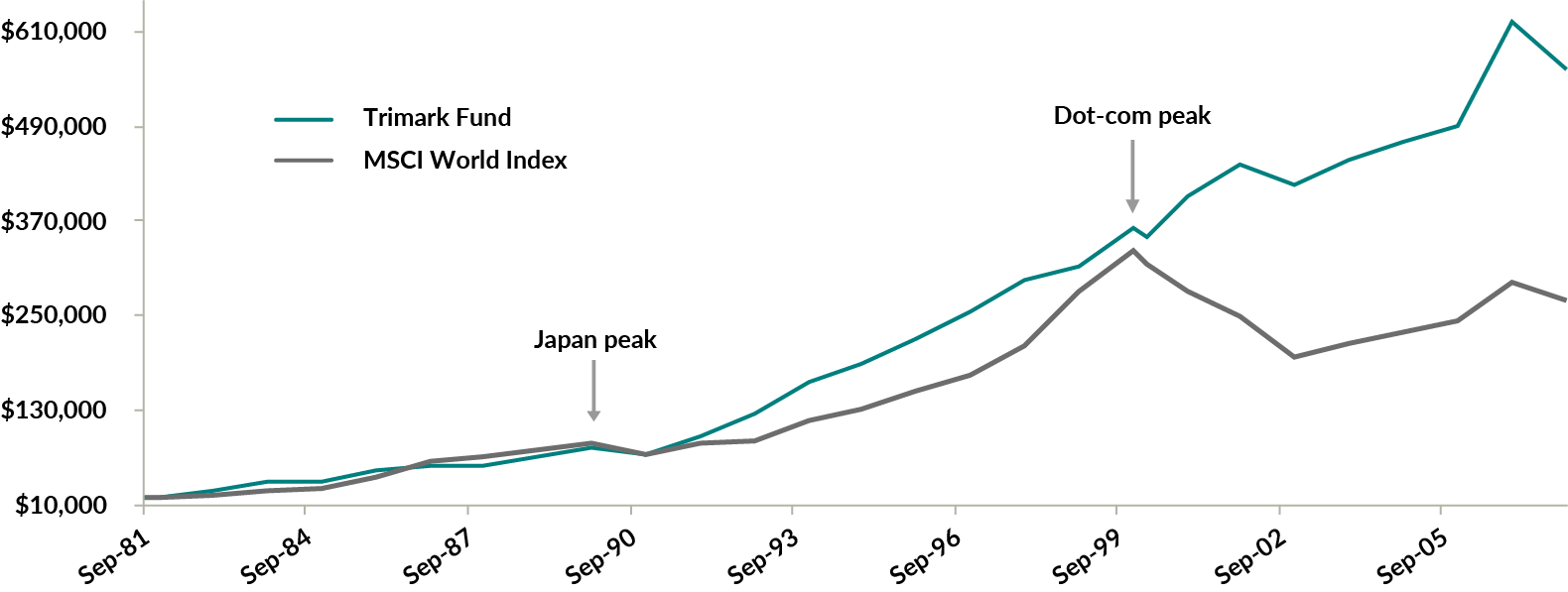

The investment approach we’ve described dates back to Bob Krembil, one of EdgePoint’s founders. It’s been successfully employed over the past five decades at multiple organizations and across various market cycles. The Taurus Fund and the Trimark Fund (now known as the Invesco Global Companies Fund) were managed according to the same investment approach between 1972 and 2007. The Taurus Fund managed to almost triple the returns of the MSCI World Index from the end of 1971 to April 1981. The Trimark Fund doubled the returns of the MSCI World Index between September 1981 and the end of 2007.ii I think we would all agree that the approach has delivered pleasing long-term returns for investors.

But here’s the catch. The approach doesn’t work every day, every month or even every year. That’s the difficult part. You have to be willing to look wrong in the short term in order to be right in the long term.

It may seem counterintuitive, but the fact that our approach doesn’t always work is a good thing for investors. If what we did worked all the time, everybody else would be doing it and our returns would get competed away. The inevitable short-term underperformance makes it difficult for others to stick with the approach, hence the approach can endure.

If you look at the history of the investment approach, it typically underperforms in markets where investors crowd into a small group of companies (we call this consensus thinking). This often happens during periods of extreme euphoria or fear in the market. By not owning the same businesses as everyone else, the approach can look foolish in the short term. Below are some examples from the first three decades of the investment approach.

Taurus Fund, Series FE vs MSCI World Index

Dec. 31, 1971 to Apr. 30, 1981

Source, Taurus: Bolton Tremblay Funds Inc. 1982 Annual Report. Source, MSCI returns: Morningstar Direct. Total annual returns measured in C$. Historical performance is not indicative of future returns. The Taurus Fund is used for illustrative purposes only to demonstrate the history of the investment approach applied at EdgePoint. The MSCI World Index is a market-capitalization-weighted index comprising equity securities available in developed markets globally. The MSCI World Index was used for comparison purposes as it represents a broad global equity universe across several developed market countries, although it may not be a fair comparison for the Taurus Fund, due to a possible small-cap exposure in the Fund.

In the chart above, you will notice that in the first four years of the Taurus Fund, it didn’t outperform the index. Why? This was the Nifty Fifty era. Investors had a belief that all you had to do is buy the Nifty Fifty stocks regardless of price. They were called the “one-decision stocks” because once bought, you never had to sell. If you bought the Nifty Fifty stocks at their peak in 1973, it would have taken a decade just to get your money back.iii

During the first 20 years following the launch of the Trimark Fund in 1981, there were two major consensus thinking themes – “Buy Japan” and the “Dot-com boom. ”

Trimark Fund, Series SC vs MSCI World Index

Sep. 1, 1981 to Dec. 31, 2007

Source: Morningstar Direct. As at July 27, 2018, Trimark Fund changed its name to Invesco Global Companies Fund. The above values are for illustrative purposes only and do not represent an actual client’s results. Total annual returns measured in C$. Historical performance is not indicative of future returns. The Trimark Fund was used for illustrative purposes only to demonstrate the history of the investment approach applied at EdgePoint. The MSCI World Index is a market-capitalization-weighted index comprising equity securities available in developed markets globally. The MSCI World Index was used for comparison purposes as it represents a broad global equity universe across several developed market countries. The Trimark Fund was managed independently of the index used for comparison purposes. Differences including security holdings and geographic/sector allocations may impact comparability.

In the 80s, when the consensus thinking was to “Buy Japan”, the belief was that Toyota was going to teach the rest of the world how to make cars forever and everyone was going to buy Sony Walkmans and televisions. It’s now thirty years later and the Japanese stock market still hasn’t recovered from its previous peak in 1989.

Ten years later, people questioned the Trimark Fund’s lack of information technology holdings. Dot-com companies were market darlings and money rushed into them. At the start of the 2000s, the market realized they were overvalued and the panic selling resulted in many people losing their savings.

So with an investment approach that successfully navigated the periods of consensus thinking, you might be thinking it was an easy time for EdgePoint to launch during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. It wasn’t.

EdgePoint’s opening tip

Many people look back at EdgePoint’s early days and assume it was a pleasing time for us to invest. What is often forgotten is how scary the environment was and the herd-like behaviour of the average investor.

The consensus thinking was that we were on the verge of a global recession and the survival of many businesses was in doubt. In that environment, investors wanted to own businesses that made them feel safe. Buy Colgate because people still need to brush their teeth. Campbell Soup is a good investment because everyone will eat soup during a recession. While these sound like good ideas, the problem is everybody else already knew the same thing about these businesses.

EdgePoint took a different approach. We looked for businesses that we believed were just as likely to survive, but were priced like they wouldn’t make it. We call those businesses “non-obvious survivors.”

What was the reward for taking an unconventional approach? From January 6, 2009 to March 9, 2009, the EdgePoint Global Portfolio declined by 22%.iv

But it’s the long-term results that matter. Investing in non-obvious survivors when others thought the sky was falling led to pleasing returns over the next decade. The EdgePoint Global Portfolio produced a 10-year cumulative total return of 337% following its November 17, 2008 inception, compared to a basket of popular “safety” names that on average only returned 158%.

| POPULAR “SAFETY” NAMES DURING 2008-09 FINANCIAL CRISIS | CUMULATIVE TOTAL RETURNS (LOCAL CURRENCY) NOV. 17, 2008 TO NOV. 17, 2018 |

|---|

Source: FactSet Research Systems Inc. Total returns in local currency. Returns measured from the inception date of the EdgePoint Global Portfolio. The above basket of “safety” names represents popular large capitalization companies from a variety of different industries with below-average volatility in their business models and, by default, their share prices. Businesses that fall into this camp would include telecommunication, pharmaceutical and packaged goods companies.

Waiting for the rebound

Now let’s fast-forward to the present. As we just experienced, 2020 was another year where at first panic and later euphoria resulted in investors flocking towards a small group of companies.

During periods of uncertainty, the time horizon of the average investor tends to shrink dramatically. As a result, we think investors today are placing too much emphasis on the near-term prospects of businesses. They’re ignoring many high-quality companies whose next three or six months might be uncertain, but whose next three-to-five years are highly predictable.

Short-term uncertainty has nothing to do with survivability or growth. We own businesses that we believe will not only survive but will be much bigger in the future. The problem is that we can’t tell you with any precision what their revenues or profits are going to be next quarter.

If you’re willing to look out a little bit further, the visibility improves dramatically. In fact, the further you look out, the brighter the prospects of these companies become. Because the herd is focused on the next three or six months, they’re ignoring many market-leading businesses that can be much bigger in the future where you aren’t being asked to pay up for that future growth.

Let’s walk through a few examples of some businesses across our EdgePoint Global and EdgePoint Canadian Portfolios to illustrate how we focus on long-term clarity over short-term uncertainty. While some of our businesses were impacted in the short term, we believe their long-term growth prospects remain intact. In many cases, the pandemic actually accelerated their growth drivers, which should result in even stronger businesses on the other side.

| Portfolio Holding | CONSENSUS SHORT-TERM VIEW | EdgePoint PROPRIETARY LONG-TERM VIEW |

|---|

EdgePoint Investment Group Inc. may be buying or selling shares in the above securities. Views represent the Investment team’s proprietary insights and research.

Investors unwilling to look wrong in the short term don’t invest in these types of companies because they might not seem like a good investment over the next few months. Fortunately, we can rely on our time-tested investment approach.

Buzzer beaters

Our investment approach has added the most value for investors when it looked the most wrong in the short term. If history is a guide, actions taken during these difficult and unpopular periods sow the seeds for pleasing long-term returns.

Unlike Wilt Chamberlain, we’re willing to look silly to other people because we believe it’s the right choice to help investors get to their Point B. The granny shot, much like our investment approach, might not always be appealing but we believe it’s effective.

Investing against the crowd is hard. Like basketball, investing is a team sport and without the right partners it would be impossible to do well. We’re fortunate to have all-star partners who recognized the opportunity this past year and gave us more capital to put to work during the downturn.

Thank you for your trust. We work hard every day to be worthy of it.

ii Source, MSCI and Trimark returns: Morningstar Direct. Source, Taurus: Bolton Tremblay Funds Inc. 1982 Annual Report. As at July 27, 2018, Trimark Fund changed its name to Invesco Global Companies Fund. Total annual returns measured in C$. Historical performance is not indicative of future returns. The Taurus Fund and Trimark Fund are used for illustrative purposes only to demonstrate the history of the investment approach. All of the funds applied the same investment approach across different companies, investment teams and members. The MSCI World Index is a market-capitalization-weighted index comprising equity securities available in developed markets globally. The MSCI World Index was used for comparison purposes as it represents a broad global equity universe across several developed market countries, although it may not be a fair comparison for the Taurus Fund, due to a possible small-cap exposure in the Fund. The Trimark Fund was managed independently of the index used for comparison purposes. Differences including security holdings and geographic/sector allocations may impact comparability.

As at December 31, 2020. Total returns, net of fees. Taurus Fund excluded since it is no longer in existence.

EdgePoint Global Portfolio – Series A

YTD: -1.16%; 1-year: -1.16%; 3-year: 2.63%; 5-year: 7.42%; 10-year: 11.58%; since inception (11/17/2008): 13.36%

MSCI World Index*

YTD: 13.87%; 1-year: 13.87%; 3-year: 11.16%; 5-year: 10.26%; 10-year: 12.63%

Invesco Global Companies Fund – Series SC**

YTD: 3.25%; 1-year: 3.25%; 3-year: 6.51%; 5-year: 7.36%; 10-year: 10.92%; since inception (09/01/1981): 11.27%

* As at October 17th, 2016 the Trimark Fund changed its benchmark to the MSCI All Country World Index.

** As at July 27, 2018, Trimark Fund changed its name to Invesco Global Companies Fund.

Source, MSCI and Trimark: Morningstar Direct. Source, EdgePoint: Fundata Canada Inc.

iii Source: Nifty 50: Empirical Research Partners, LLC. In US$. The movement is market-capitalization weighted. The Nifty 50 were a collection of 50 companies regarded as solid "buy-and-hold" equities.

iv EdgePoint Global Portfolio, Series A. Total return in C$.

v Dark kitchens, also known as ghost kitchens, are kitchens designed for food preparation at location that do not have direct customer interaction/dine-in.

vi The Canadian Press, “Fairfax's Prem Watsa spends nearly US$150M to buy more shares.” BNNBloomberg.com, June 16, 2020. https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/fairfax-chairman-prem-watsa-spends-nearly-us-150-million-to-buy-more-shares-1.1451233.