Active management’s merits (or lack thereof) are widely debated. For good reason. Active managers seem to have a pretty lacklustre track record. Study after study has shown that the vast majority of actively managed funds lag their passive counterparts over extended periods, appalling considering active managers charge higher fees. Investors can find themselves paying more to make less.

On the flip side, passive management, or indexing, centres on the idea that the stock market is “informationally efficient” and that businesses always trade at their fair value because everything there is to know about them is reflected in their stock prices. If true, consistently beating the market – the active manager’s mission – would be nearly impossible. Of course, those relatively poor returns of active managers have been held up as proof that this is indeed the case. Index funds instead merely try to match market returns. (Spoiler alert: we believe active management, while far from easy, can be a very successful approach if it’s genuinely active).

Another pro-passive argument is that even if you could repeatedly do better than most investors, the odds of spotting that outperformer in advance are slim. Like finding a needle in a haystack, they say. Since the average investor can’t put in the extensive effort needed to find a suitable active manager, passive investing notwithstanding its limitations seems to be the one viable option. Or is it?

Assessing activeness

A pair of former Yale finance professors (Martijn Cremers and Antti Petajisto) recently addressed a fundamental flaw in active management studies. As it turns out, funds typically included in research are essentially passive investments thinly veiled as active ones. In Canada, 12 of 20 equity funds are what’s called “closet indexers.” That’s right – more than half of the usual sample set of “active” funds don’t actually qualify on closer look.i This miscategorization obviously skews comparisons between active and passive.

So Cremers and Petajisto came up with a remarkably simple way to express a fund’s activeness. Active share measures the differences in holdings between a fund and its index. The higher a fund’s active share number, the more it departs from its index based on the selection of businesses in its portfolio.

Thanks to the brains behind active share, identifying and tracking truly active fund performance is now relatively easy to do.

Know the reward

Cremers and Petajisto also discovered that funds with the highest active share have outpaced their benchmarks by 3.64% annually.ii They made 1.4 times more money for their investors over a 10-year period (assuming an average market return of 9%). Predictably, funds with the lowest active share were left behind.

Makes sense. A fund that largely mirrors its index should post index-like performance. Their holdings are that similar to each other. Low active share funds really can’t be expected to do more. They’ll probably do less because fees and trading costs create an additional performance hurdle to clear, unlikely for funds that are otherwise carbon copies of their benchmarks.

Active share drives home the point that outperformance potential decreases as resemblance to an index increases.

Not all managers with high active share will automatically beat their benchmarks. All we know is that the average performance of highly active managers has exceeded the average performance of managers with low active share.

Bottom line: there’s a very real possibility that when a manager bets away from an index, it’s a bad bet. If you rely exclusively on active share as your guide to fund selection, you may still pick an underperformer.

Hugged an index lately?

At the same time, a fund’s active share is hands-down ideal for signalling whether an active fund manager is more like a closet indexer and perhaps someone you should avoid. With higher fees comes the reasonable expectation of something in return, including a knowledgeable and experienced manager who conducts in-depth analysis on every business they own. You should also expect stronger long-term performance.

Closet indexers think it’s okay to charge fees for active management when in reality they deliver an index-like experience. Their investors don’t get much bang for their buck. A fund managed by a closet indexer will have an active share of between 40% and 60%. These copycats are trying to manage their own career and reputational risk. For them it feels safer to track an index than to take on the greater risks incumbent with active management.

And it’s no wonder. Almost half of fund managers in one survey said they feared losing their job if they underperformed the market for as little as 18 months.iii If past performance is no guide to picking the best managers, then a few years of underperformance may not be cause enough to fire a manager either. Yet investors quickly give up on funds, previous strong performers or not, when the returns aren’t there.

Their behaviour influences fund managers, who in turn hug their benchmarks to try to minimize the risk to their business of investors’ money walking out the door. Explains why there are more closet indexers today than at almost any other time in history. Because let’s face it, looking wrong isn’t as bad when the crowd looks wrong with you.

Here’s the thing – owning a closet indexer you think is an active manager is like shelling out for a luxury car and getting an economy class. It’s imperative to put your funds to the active share test. Know how your money is being managed and don’t overpay for investments that are only halfway in the game.

Though active share on its own can’t predict which funds will outshine and identifying surefire winners in advance will remain impossible, investment success increases when certain attributes are present. For example, smaller, more nimble funds are predisposed to outperforming larger ones. That’s because big funds managing a lot of money are more cumbersome and have limited investment potential. It’s harder for them to build meaningful positions in small businesses.

Funds also stand a better chance when their managers have their own money invested in them. This helps to ensure an alignment of interests with investors. Lower fees help too obviously.

Another indication of active management to use in tandem with active share is tracking error. Whereas active share compares a fund’s holdings to its index’s, tracking error does so with returns. It can be the trickier of the two concepts to grasp but still worth keeping in your back pocket as a way to reveal what lies behind a fund’s active share number.

Active share + tracking error

Tracking error is the difference between a fund’s return and that of its index’s. Low tracking error indicates that a fund is performing much like its index. High tracking error indicates the opposite.

Tracking error alone can’t be linked to performance. However, a positive correlation between highly active funds and lower tracking error does exist. The two attributes combined have led to improved returns.iv

The weakest-performing funds have been those with the highest tracking error at varying levels of active share, including closet indexers.

High tracking error is characteristic of fund managers who make “factor bets” or “concentrated stock picks,” fancy terms for approaches based on investing in various categories to capitalize on price anomalies or strong market sectors. Basically, taking top-down views of the market. These investments have turned out to be relatively riskier and any outperformance has been unsustainable. Concentrated stock pickers beat their benchmarks, but only before fees. Factor bet funds have performed the poorest and “destroyed value” for their investors.v

In contrast, more diversified stock pickers take a bottom-up view. They invest by choosing individual equities that they believe will outperform. Diversified stock pickers have been the only ones to generate excess returns after fees and expenses and they’ve done so with less risk. This suggests that high active share is desirable if it’s the result of stock picking and less desirable if it’s the result of top-down market calls that show up as high tracking error.

Assessing past performance isn’t nearly as constructive as knowing how your money is being invested. Most importantly, active share and tracking error together provide insight into a fund’s management style to help you recognize the type of active management you’re getting. According to the research, you should be looking for stock pickers as they have the greatest potential to add value.

Active share + turnover

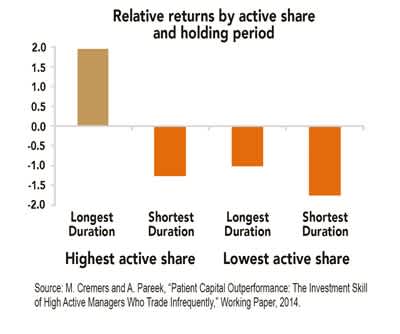

Longer holding duration is another common characteristic of highly active managers that has led to outperformance. Also called turnover, this measure reflects the amount of time a stock spends in a fund. In addition to the link between active share and tracking error, Cremers has uncovered that funds with the best relative returns have had both high active share and at least a two-year holding duration.vi

In fact, Cremers identified highly active funds with longer holding periods as the only group with a history of outperformance. They did better by an “economically remarkable” 54% cumulatively over the 19 years he studied. He found no evidence that even the most active managers with short holding durations or frequent trading beat their benchmarks. Rather, high turnover active funds were on average quite unprofitable.vii

It’s true that today’s market participants are increasingly nearsighted, narrowly focusing on what's just happened, is currently happening or about to happen. In this environment, taking the long view as an active manager is a strong competitive advantage.

The lowdown on low turnover

Imagine spending your life savings on a million-dollar business to support your family and then exchanging it for a different business soon after, and continually repeating the process. As crazy as it sounds, that’s exactly what short-term investors do. From 1980 to 2013, the average annual turnover rate of equity funds in the U.S. was 61%, meaning stocks are held for 18 months on average.viii That’s a lot of fund managers who lack confidence and conviction in the businesses they own, and their returns reflect it.

A longer holding period offers the latitude to develop a thesis about a business that isn’t reflected in its current stock price. One drawback of heavy turnover is that it can cut short a fund manager’s best and most enduring investment ideas. Those with a longer-term horizon understand that the market will eventually recognize the potential of the businesses they own assuming their ideas about them are correct. This difference in time perspective provides opportunity for active managers to add value.

The more you know, the better you get

Active share research has made it clear that active funds can’t be painted with the same brush, that skilled, long-term stock pickers with longer holding periods can beat benchmarks and that index huggers rarely do. To be sure, active share has a place in every investor’s toolkit, along with tracking error and turnover. A highly active fund with low turnover and tracking error is more likely to outperform than a fund with none of these attributes, plain and simple.

But ultimately even multiple measures won’t work like a crystal ball to predict exactly how an investment will behave and both quantitative and qualitative factors come into play. At its essence, evaluating a fund manager is about understanding how they invest, ensuring it fits your investment needs and expectations, and the extent to which they do as they say – the most important metric of all.

ii Ibid.

iii Sullivan, P., “The Folklore of Finance: Beliefs That Contribute to Investors’ Failure,” New York Times, November 14, 2014.

iv Cremers, M. and Petajisto, A. “How Active is Your Fund Manager?” Yale School of Management, 2006.

v Ibid.

vi Cremers, M. and Pareek, A., “Patient Capital Outperformance: The Investment Skill of High Active Managers Who Trade Infrequently,” Social Science Research Network, 2014.

vii Ibid.

viii Investment Company Institute, “2014 Investment Company Fact Book. A Review of Trends and Activity in the Investment Company Industry,” 2014.