At a recent dinner, the topic of long-term performance came up. A great question came from a partner who’s been invested with us since our early days:

“You’re coming up on your 15-year anniversary. 95% of managers underperform over that type of time frame –

what did you do differently?”

I defaulted to talking about our investment approach – the idea of having a proprietary insight and buying growth without paying for it. It was a very unsatisfying answer for both of us. It didn’t explore the reasons why we could generate those insights in the first place, or give confidence that we’d continue to come up with such proprietary insights going forward.

Our investors deserve a proper answer to this question. We don't always get second chances, so I'm taking this opportunity to share the answer I should have given to the partner.

People frequently talk about things without being specific about them. In this case, I’m referring to our structure, the very foundation of our organization. While we often discuss elements of our structure, we rarely talk about it directly or about its importance in achieving our long-term success.

Following that dinner, I made a list of structural elements that were critical to our success. While there were many, three aspects stood out as particularly important: compensation structure, the decision-making process and company ownership.

Compensation structure

Charlie Munger has a famous quote, “Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome.” The quote is as profound as it is simple. Countless millions are spent on compensation consultants every year, and yet the world is awash in poorly structured incentives.

In the realm of economics, there’s an intriguing concept called the "Cobra Effect." This peculiar term takes its roots from an incident that transpired during the British colonial rule of India. The British administration at the time found themselves dealing with a surging population of venomous cobras in Delhi. To combat this issue, they introduced a bounty for every delivered cobra skin. The initial results of this strategy were promising as the cobra mortality rate surged.

However, the course of this plan took an unexpected turn when resourceful locals realized they could breed cobras solely to claim the bounty. Upon uncovering this exploitative practice, the government swiftly abolished the reward program. The cobra breeders in turn released their now-valueless snakes into the wild, inadvertently boosting the cobra population beyond its original number and exacerbating the problem. Thus, the term "Cobra Effect" was coined.

The Cobra Effect is a striking demonstration of what economists call "perverse incentives," those that lead to outcomes contrary to the original intentions of the system. Evidence of perverse incentives is woven into the fabric of our society, even in the seemingly mundane area of asset management compensation! All money managers are paid based on “performance.” But here's the catch – while performance-based compensation may seem intuitive, the real question is what should this performance be measured against?

Many money managers are paid to beat the market and, as such, their success is measured against a designated benchmark that serves as a market proxy. A substantial amount of their compensation often comes from measuring performance relative to that benchmark. However, this “logical” approach may spawn its own Cobra Effect.

To illustrate, let's envisage a scenario. Company A is one of the 1,500 constituents of the MSCI World Index.i An investment manager, benchmarked against the MSCI World, is ambivalent about Company A. The manager faces two choices, with four scenarios based on how the company’s stock performs:

Given the manager's lack of conviction about Company A, the safest bet is owning the company and accepting the market returns, irrespective of whether it’s good or bad.

Compensating managers based on their performance relative to a benchmark inadvertently redefines risk. At EdgePoint, we see risk as potential for permanent loss of capital. Meanwhile, instead of it being about potential financial loss, managers who are judged according to a benchmark see risk as deviating from that benchmark. It's common to hear managers discussing the “risk” of not owning a particular company or sector. This notion seems perverse, doesn't it? How can the absence of something constitute a risk? Unless the managers are thinking about a permanent loss of their capital (i.e., their bonus).

This is the Cobra Effect rearing its head in asset management. A benchmark-relative compensation structure breeds managers who often mirror the benchmark itself. This is an unintended consequence that strays far from the original intent of the incentive system, which is getting clients the best possible return.

At EdgePoint, we firmly uphold the conviction that to outperform a benchmark, you must dare to look different. Our present-day active share is a testament to this belief, standing at 98% for the EdgePoint Global Portfolio.ii Like other firms, we believe performance should form a significant part of remuneration. In fact, it’s the highest contributing factor for much of our Investment team’s compensation. Where we’re proudly different is in our performance metric – we measure it relative to our industry peers.

The structure we have in place is straightforward. To earn a full bonus, our team needs to deliver performance that sits within the top quartile over a rolling five-year period relative to our peer group. Should we find ourselves in the second quartile, our compensation takes a noticeable hit. In the event of landing in the fourth quartile, it drops to nil. With hundreds of funds making up our peer groups and information about their holdings being both limited and delayed, we find ourselves unperturbed by index weights or peers' holdings. Our focus is solely on achieving absolute returns, not on how our holdings list stacks up against others.

Our compensation system discourages us from investing in stocks that we don't understand. Instead, we direct our energy towards cultivating a curated portfolio of businesses that we understand deeply. We’re incented to seek out companies that are overlooked by our peers, ones that are frequently smaller weights or unrepresented in major indexes.

However, it’s crucial to understand that compensation isn’t the sole factor tying us to our investment partners, nor is it limited to the Investment team. Excluding our institutional associates, EdgePoint employees form the largest single group of investors in our Funds, with over $363 million invested.iii For most of our partners, this investment forms a considerable amount of their personal wealth, and it sits right alongside our external partners' investments in the same products.

In addition to investing alongside our clients, every EdgePoint employee has the opportunity to buy into the business. This isn’t a free option – it’s an investment EdgePointers make with their own money. By buying into the business, the success of our internal partners becomes dependent on the success of our external partners – which is how it should be.

Decision-making process

Here's a thought experiment to consider:

Suppose you find yourself in a precarious situation where you must outperform the market over the next three years. Failing to do so isn’t an option; your life quite literally hangs in the balance. You have two strategies at your disposal, and you must decide at the outset which you will use in an attempt to beat the market:

Option 1: You must make two to three investment decisions each year

Option 2: You must make 200 to 300 investment decisions each year

An investment decision is simply to buy or sell, and you can make these decisions at any time in the year. You might choose to make all of them on the first day or distribute them evenly throughout the period. The choice is yours, but you must utilize all your decisions annually. Now, take a moment and decide which strategy you would employ.

From my experience, over 90% of people gravitate towards the first option. It's undoubtedly the choice I would make, and the rationale is straightforward – worthwhile investment opportunities are rare. The more decisions you're obliged to make, the less time you can devote to each one to discern if it's truly a sound choice.

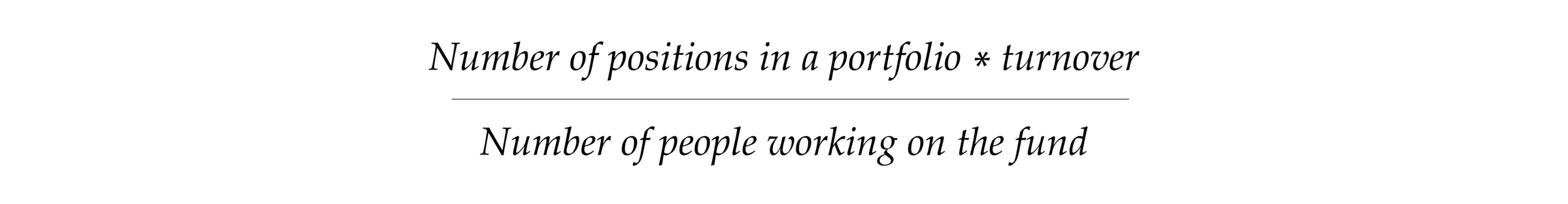

While this idea resonates with many people, it isn't as prevalent within the investment industry. There's a simple way to measure decision-making intensity across different funds:

For instance, if a fund has 100 positions and a turnover of 50%, that implies 50 decisions per year. If two people are managing the fund, it's roughly 25 decisions per person. However, in many cases, managers supervise multiple funds, which should also be factored in.

Applying the same equation to EdgePoint’s Portfolios, we find that each team member is responsible for coming up with two to three ideas per year. Many people intuitively understand and prefer this strategy. By focusing on fewer decisions, we remove distractions and make informed choices. This can boost our chances of finding valuable investments and simultaneously avoid potential losses.

Warren Buffett encapsulates this strategy as the “punch card” approach. Imagine starting with a punch card consisting of 20 slots, each representing an investment opportunity. Every time you make an investment, you punch out a slot, leaving you with one less investment choice to make in the future.

While we don't impose a strict limit on the number of investments we can make, our business model is based on the principle of limiting the number of decisions we must make. This philosophy manifests itself in several ways:

Offering a limited number of funds

Focusing on concentrated holdings within funds

Striving for a long average-hold period for investments

Compensating Investment team members independent of any benchmark and focusing on five-year returns

Company ownership

In Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money, he makes an interesting observation about Buffett. At the time of the book’s writing, Buffett’s net worth was roughly US$84.5 billion. Of that, US$84.2 billion accumulated after his 50th birthday. In other words, 99% of his wealth was created after the age of 50.iv

While Buffett is one of the greatest investors to have ever lived, you’ll miss an important key to his success by just looking at his annual returns. More informative is his number of annual returns – his wealth is a function of being an exceptional investor for an exceptionally long period of time.

Thinking and acting long term isn’t always easy, especially for publicly listed fund companies. Investors expect updates every 90 days that show continuous improvement. This tends to create a culture that’s short-term oriented. For asset managers, the solution is often to launch more funds to raise more assets (and not coincidentally, increase the total fees charged to manage them). These funds will typically be based on whatever trend is hot at the moment and not what offers the best long-term opportunity to compound capital. This forces their investment managers to cover more investments and make more decisions. With more choices to make, the managers become more inclined to look like the index. This is essentially the last 30 years of mutual fund history.

To our great advantage, EdgePoint is a private company owned by its employees. We officially only answer to ourselves and our board, but unofficially we’re responsible to our investors. Similar to the Buffett example, we understand that to maximize our partners’ wealth (both external and internal), we must focus on opportunities that allow us to compound at the highest risk-adjusted returns for the longest possible duration. These opportunities will look different depending on asset class, but ultimately, we would never offer a product that we wouldn’t be willing to put our own money into.

Conclusion

We have said investing is deceptively simple, and I think that description applies to how to set up a fund company for the mutual benefit of its employees and its clients. Compensating our Investment team based on performance relative to our peers allows us to focus on looking for the best opportunities for our investors, not just force us to keep pace with an almost arbitrary collection of companies that make up most indexes.

We then try to limit mistakes in two distinct ways. The first is by limiting the decisions that team members must make. We do this by only offering a small number of concentrated funds with a willingness to commit to holdings for longer periods, allowing the market to recognize what we see in these holdings and for the share price to reflect it accordingly. The second is by limiting who gets to influence the Investment team’s decisions, and we achieve this by remaining a private company. Our structure avoids having to answer to shareholders who would want us to make decisions that benefit them, such as increasing fees and offering more funds, to the detriment of our end clients.

As mentioned in the introduction, I’m glad the partner asked me that great question, because it compelled me to reflect deeply on our investment approach and what makes us different. Anything built to last needs a solid foundation, which is why we believe our approach has worked for over 50 years. For almost a decade and a half, we’ve applied it at EdgePoint and structured it in a way that we believe will allow us continue helping our clients achieve their goals into the future.