Should I stay or should I go? – 3rd quarter, 2014

We're not quoting the Clash with the above question. Instead, we're quoting a question we've been hearing frequently this past year that refers to whether or not those fortunate enough to stay invested during the past five years should take some profits now that the market has risen. Other recurring questions have been: “Should I wait for the market to drop before investing more?” “When should I buy back into the market?”

The huge fear of loss ingrained in many investors' minds has made the industry more anxious, which means these questions are more frequent today.

Problem questions

There are two problems with these questions.

The first problem is there's an underlying assumption that the market is one cohesive organism. The reality is, “the market" is a collection of hundreds of very different businesses in a multitude of different industries, with different balance sheets, different management teams, different growth opportunities, different competitors, different valuations and the list goes on. Super computer IBM Watson would short circuit, stuck in an infinite loop, attempting to answer these questions while properly analyzing the data.

A second problem is there’s an assumption that someone knows the answers to these questions. There must be a belief in the existence of a crystal ball-carrying market timer. Success in investing will never be achieved if you believe such a skill exists. Those asking these questions likely think success must come from being all-knowing. As hard as it might be to believe, successful investors know that it more often comes from not only knowing they don't know it all, but also knowing what they don’t know.

When someone develops the crystal ball to answer such questions, we'll buy one and all know the answers thus rendering the information useless. Kind of makes the whole endeavour pointless, doesn’t it?

We're going to try to address why these questions aren’t worth worrying about. If we succeed, you'll understand the futility of market timing. And if we don’t, please direct your questions to those who claim to be in possession of a crystal ball. These claims can be a very prosperous windfall for the pretender. Unfortunately for investors, there are many pretenders out there.

IBM Watson’s dilemma

Let’s assume Patsy, an average investor, has money to invest in the U.S. market, but is wondering when the best time would be over the next year.

Picture all the work and uncertainty Patsy has to manage when trying to forecast the results of just one company. How many different products does it offer? What will the prices of all those products be? How many of each product will the company sell next year? Will the increased research and development expenses translate into new revenue-generating products? What strategies will competitors employ that could affect these assumptions? Has a competitor changed strategy lately or become more price competitive? Should we read anything into the CEO selling half of their stock? How will the company cost structure change next year? Will its financing costs change? What about its tax rate or size of its pension deficit?

The above paragraph outlines a small fraction of the questions Patsy would have to ask about just one company. Even if Patsy asks all these questions, could she, the smartest person in the world, or the world’s most powerful computer program get all the answers right? If they did, which they won’t, they’d be missing the hardest part, which is how others will interpret the eventual results of this company? In other words, how will the company be valued next year after time allows market participants to see the actual results to the questions above?

Should Patsy be silly enough to attempt this for one company, she’d then have to do it 499 more times to complete her forecast of what the S&P 500 Index will do next year and how it will be valued. We’d wish her luck if she tries…luck being the operative word of course.

Is the market really up?

To add more fuel to the fire, here’s another reason why these questions could be ill-timed as well as irrelevant. These questions are often more prevalent when the market is up. At the end of the quarter, major market indices were up between 4% and 12% year to date. The thought being if the market is up, perhaps you should wait until it’s down until you invest. Remember in the previous section when we said the market is simply a collection of many different businesses? Keeping that in mind, let’s examine the belief that the market is up.

A total of 177 (or 35%) of stocks in the S&P 500 Index and 82 (or 33%) of stocks in the S&P/TSX Composite Index are down this year.

Looking at smaller companies, 1,314 (or 66%) of Russell 2000 stocks are down this year, while 90 (or 41%) of the stocks in the S&P/TSX Small Cap Index have declined.

Buying stocks whose prices have fallen should never be your criteria for buying. But if it makes you feel better when buying, 1,663 companies are available for you to look at. That works out to 60% of the collective stocks in these indices!

Is the market really up when over half the stocks are down? Luckily the question is irrelevant. But would it change the view of those posing the questions at the beginning of the commentary? I suspect it would.

Rosie Rotten

Charles Schwab & Co. published a report on December 16, 2013 on the futility of market timing. The link is here, but I'll summarize the analysis and findings below.

It created five hypothetical long-term investors, who each received $2,000 at the beginning of each year for 20 years ending in 2012.

Peter Perfect was the perfect market timer. He invested in the market every year at the lowest monthly close. Each year he was somehow able to determine this date.

Ashley Action simply invested her money as soon as she received it.

Matthew Monthly divided his $2,000 into 12 equal portions each year and invested at the beginning of each month. In other words, he was the dollar-cost averager.

Rosie Rotten had horrible luck. She invested her $2,000 each year at the market’s peak. She happened to hit the market high every year for 20 years!

Larry Linger left his money in cash every year, always thinking there’d be a better opportunity to invest in the future when stock prices were lower.

Here were the results after 20 years:

| Hypothetical investors | Growth after 20 years |

|---|

When looking at the results above, it’s Rosie Rotten’s results that are most encouraging because an investor couldn’t possibly do as poorly as Rosie even if they tried. The only person who failed is the person who didn’t try.

Before I lose you, you might be thinking this 20-year period was hand selected, but the author looked at 68 separate 20-year periods dating back to 1926, finding similar results across almost all timeframes. In 58 of the 68 time periods, the rankings were identical to what you see above. In the other 10 periods, “invest immediately” never came in last. It was in its normal 2nd place four times, 3rd place five times and 4th place only once.

The analysis also looked at all possible 30, 40 and 50-year time periods starting in 1926. Investing immediately and dollar-cost averaging always seemed to end up with satisfactory results.

Unfortunately, Schwab missed the most important hypothetical character, Dennis the Dart Thrower. As his name suggests, he selects the timing of his investment each year by randomly throwing darts at a calendar. He’d likely always outperform Rosie.

Throw a dart, invest at once, invest at the worst time each year or dollar-cost average. It hasn’t mattered when you invest, only that you do invest.

What if Rosie was worse than rotten?

Some readers might say that since Rosie was buying each year, there were many good years to buy, even if she happened to make purchases at the worst times in those years. In other words, in the good years, Rosie's bad purchases more than offset some of her really bad purchases made during the really bad times to buy.

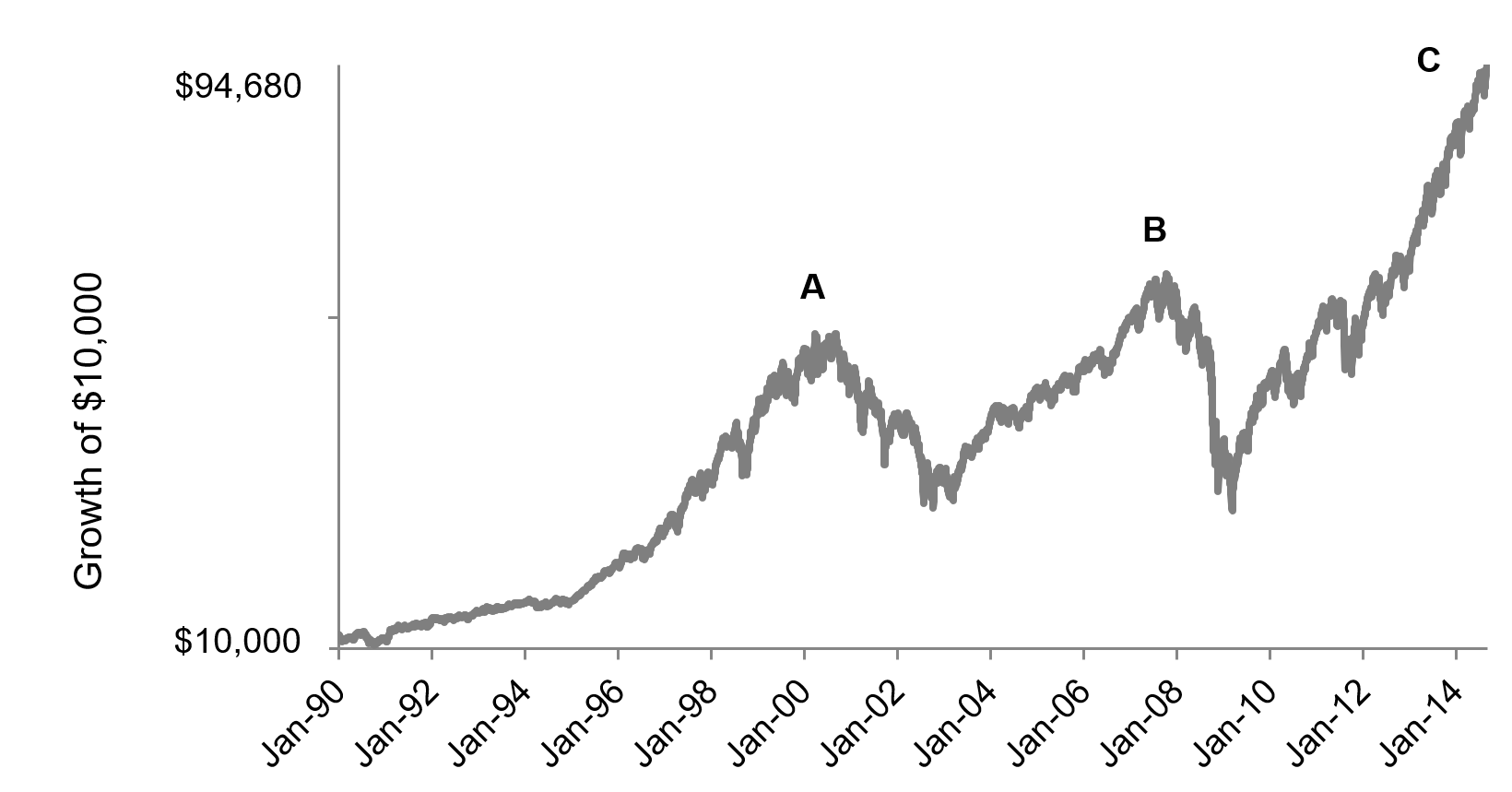

Let's look at the past 24 years, which happens to include two of the worst market downturns in history. And let's assume Rosie is so unlucky she was only able to make two purchases in the past 24 years. Her first purchase was at point "A" on the graph below, which was the peak of the S&P 500 in the year 2000.

A little gun-shy from that experience, she only gained confidence to get back into the market after it rallied past its previous highs in 2007. Her second purchase is seen as point "B" on the chart:

S&P 500 Index - Growth of US$10,000

Jan. 1, 1990 to Sep. 30, 2014

Source: Bloomberg. S&P 500 in US$. Growth of $10,000 as at September 30, 2014. Point A to point C represents August 31, 2000 to September 30, 2014 and point B to point C represents October 31, 2007 to September 30, 2014.

Rosie's annualized return from point A to point C was 3.9%, and her annualized return from point B to point C was 5.9%. This is hardly stellar, but could anyone have possibly done worse than this during the past 14 years? Believe it or not, many have. The one thing that the worse than rotten investors have in common is they think they know how to time market entry and exit points.

The benefit of lower prices

The crazy thing about investing over the long term is we benefit dramatically when stocks go down. That’s even the case if we already own the stocks before they go down! Knowing that makes market timing even more futile.

Here’s an exaggerated example to make this point:

Suppose you invest $100,000 in the S&P 500 Index. Let’s pretend there are two scenarios. We’ll call the first scenario “rocket ship” and the second scenario “submarine.” In the “rocket ship” scenario, the market goes up 300% after the first year of your investment. Under the “submarine” scenario, the market drops 70% after the first year.

Let’s assume these moves stick and stocks don’t rally back in the submarine scenario, nor do

they fall back down in the rocket ship scenario. Let’s also assume valuations stay at these levels and the index grows by 5% per year in each scenario, which would match an assumed earnings growth for the market over the long term. We also assume dividends are reinvested. With only 5% earnings growth, companies will have more money to deploy for dividends, so we’ll assume a 3% dividend yield in the first year followed by a 5% dividend growth rate in each subsequent year.

The cumulative effect of reinvesting dividends each year in cheaper stocks (i.e., the submarine scenario), helps you generate a return of 11.0% in the submarine scenario compared to 10.7% in the rocket ship scenario. Considering that after year one the rocket ship scenario had 13.3 times more money invested than the submarine scenario, and you didn’t invest any new money, that’s an incredible feat! Despite the rocket ship scenario having a massive head start, the simple ability to reinvest your dividends at a more attractive price in the submarine scenario allows you to catch up.

What if valuations revert to normal (let’s say 16 times earnings) in year 30? In that case, the annual return for the rocket ship scenario would only be 5.9% per year. The submarine scenario would deliver a 15.8% per year return over that same 30-year time period. The discrepancy in returns would be even greater if you were able to invest fresh proceeds into the market each year.

Reinvesting your dividends, or adding to your investments, has a much smaller impact the more expensive your investments are. These additional investments make a massive difference if stocks are lower during your holding period. Thus, embrace and hope for a few down markets.

With that knowledge, you should always embrace the down market when it happens, but you shouldn’t wait for it to happen pretending you know how to time markets.

Conclusion

Though many global stock markets are close to new highs, we haven’t encountered a plethora of euphoric, complacent or risk-ignorant investors in the stock market despite the near tripling of many stock indexes from the 2009 lows. Perhaps it’s because, as we mentioned earlier, the majority of stocks are actually down this year. Both of these are good news.

Don't get us wrong. There are many reasons for investors to be frightened. There are excesses in parts of the stock market, massive dislocations in fixed income and credit (as Frank later addresses) and many overvalued stocks. But there are also numerous opportunities available at more than reasonable prices. There's always a deal somewhere. Sometimes you just have to look harder than others.

The future is bound to be uncertain and will inevitably be volatile so trying to forecast the timing of macro ups and downs is pointless. Understanding the companies we own and the sensitivity of each company's earnings to a wide range of events is a far more fruitful endeavour.

We'll lose by saying that for us, it’s most comfortable to be invested when confusion reigns and less comfortable to be invested when things are certain. Dispute is both a virtue and a necessity should you want to outperform. Confidence should be treated like the plague. Today, confusion still reigns.